- Home

- Kirsty Murray

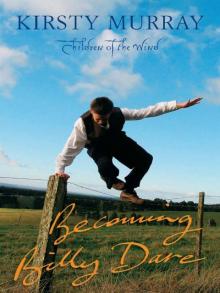

Becoming Billy Dare Page 14

Becoming Billy Dare Read online

Page 14

‘Now I've work to finish before you can turn in,’ she said. ‘there's some magazines, Table Talk and The Lorgnette over there. I buy them for my customers, to keep them busy when they come for a fitting. Or you can get the Argus from the dining room.’

‘Ill read to you while you work, if you like,’ said Paddy.

Paddy sat on the chaise longue reading out loud while Bridie busily finished off sequined outfits for the Christmas pageants. The costumes glittered as her hands moved swiftly across the fabric. For a moment, as Paddy read, he could almost imagine he was home again. If he kept his eyes on the page, he could pretend that the old woman quietly sewing wasn't Mrs Bridie Whiteley, but his own mother, grown old with missing him, and here he was, like a storybook hero, returned from years of adventuring. But when he looked up, everything was strange and unfamiliar.

‘Billy, are you all right?’ asked Bridie. She put her sewing aside and gazed at him intently with her sharp green eyes.

‘I was thinking about home, about my mam,’ he said softly. ‘But I can't be thinking about everything that's lost. I can't be living in the past.’

‘No, you're right there. But the past is always living in you and it's only lost if you won't remember it.’

‘It hurts to remember.’

Bridie reached out and rested her hand on Paddy's arm. ‘You can make a new life for yourself, Billy. Lord knows, to survive in this world, we all make our lives over again and again. But one day, when you've made your new life, those old memories will be precious. Precious as gold.’

‘It doesn't feel like gold now. It feels like fire. Like everything's burnt and black.’

‘When I was your age, I saw men risk everything in their search for riches. Some of them made fortunes and some of them lost everything. But what I found is that real gold, the most precious thing we truly have, runs like a deep seam in our hearts. One day, you'll understand that. There's pain in it now, but one day you'll see that out of the fire comes the purest gold.’

As the days at Charity House slipped by, Paddy's bruises healed and he started to feel stronger. Bridie kept him busy for much of the mornings but in the afternoon she would send him on errands around Fitzroy or into the city and then he was allowed to do as he pleased. Sometimes he'd bump into Nugget and they'd idle away an hour or two together in Bourke Street. It was easy to forgive Nugget, even if it was hard to trust him. Nugget claimed he preferred the street to living with Bridie, but as the weeks went by and Paddy became more settled in Fitzroy, he grew envious.

‘Next thing you know, she'll be adopting you proper. Everyone reckons old Mum Whiteley's got a fortune tucked away somewhere. They reckon she owns Charity House outright and that she's got a secret stash of gold underneath the floorboards.’

‘I don't see how she could be rich. She's always giving things away to anyone who asks.’

‘You're right there. In ‘93, when the depression was worst, people starving all over the city, I reckon Mum Whiteley fed half of Fitzroy. My old lady, she never had any food in the cupboard, but we could count on Mum bringing bread and mutton. I don't know. Maybe it's all a dickon pitch to kid us, but the old lady is sweet on you, that's for sure, and your worries are over.’

Paddy felt he still had plenty to worry about. He had no money, no job and no idea of what he was going to do next. But he was starting to feel that maybe he'd found a home.

On a bright December morning, several weeks after Paddy had arrived at Charity House, Bridie handed him two baskets loaded with materials and announced that she needed a porter for her morning's work.

The theatres were empty and the foyers in darkness as they walked along Bourke Street. Mum led Paddy into a lane and knocked on a stage door. Then they made their way along a labyrinth of narrow hallways. In a crowded, damp-smelling dressing room, three women were brushing each other's long hair. They all wore white leggings decorated with blue and silver beads and the tallest woman wore a long cape heavily embroidered with lions and unicorns. Each wore a vest with symbols of the British Empire embroidered across the front. Paddy recognised the Irish harp on one. When the actress saw Paddy staring at her chest, she winked at him. Paddy blushed and looked away while Mum set to work burrowing into her baskets to put the finishing touches on their costumes.

‘Where'd you find this little helper? He's a handsome devil, Mum,’ said one of them, pinching Paddy's cheek.

‘Leave him alone, ladies,’ said Bridie, bending low to adjust the hem of Scotland's cape.

The ladies of the Empire winked at Paddy. When Bridie tried to adjust the front of their costumes they angled their bottoms in Paddy's direction and wiggled them until Paddy was scarlet with embarrassment.

Outside in the street, Bridie glanced at Paddy and chuckled. ‘Well, I should have known better than to take a boy your age near that lot. Mercy, what a palaver! I must remember to keep you away from the theatres!’

‘Maybe I should get a proper job, Mum,’ said Paddy.

‘I've been thinking about that myself, Billy,’ said Bridie. ‘I've been thinking that perhaps in February, when the school year starts, you should be going back to your studies.’

‘What!’ said Paddy. ‘I can't go back to school. I'm too old. And besides, there's no money for the fees. You can't be paying for me to go to school.’

‘I've had a word to Father Ryan and he said perhaps there's some help to be had from the Hibernian Catholic Benefit Societies for a boy with so much promise.’

Paddy laughed even though he was annoyed. There was nothing that would induce him to return to school, to floggings and long hours in a classroom.

In February, Paddy was relieved to discover that Father Ryan hadn't been able to help Bridie find a scholarship. As Paddy was nearly fifteen, he was too old for the state schools, so nothing was settled upon. Paddy kept helping around Charity House, running errands and spending his afternoons exploring the city streets with Nugget. Spending time with Nugget was an education all in itself. As the months slipped by, Nugget taught Paddy how to fight, how to play two-up and how to blow smoke rings.

On a night of unexpected rain, Paddy woke to the noise of someone slamming the iron gate and stumbling up the front steps, swearing. The brass knocker banged forcefully. Paddy pulled his trousers on and went out into the passage. Bridie was there before him. She looked older in her dressing gown with her silver hair hanging loose over her shoulder.

‘Should we open the door?’ asked Paddy, nervous at the ferocity of the knocking.

‘Aye, it's sure to be Eddie,’ she said undoing the bolt. ‘It's about time he came home.’

The man on the doorstep pulled off his trilby and shook the rain from a thick mane of curly red-brown hair. It was the same elegant dandy that Nugget had tried to pickpocket all those months before. He slouched over the threshold, muttering something incomprehensible, and fell flat on his face in the hallway. Bridie looked at Paddy and grimaced.

‘Help me, will you, Billy, there's a good lad. I suppose I'll have to make up a bed for him on the floor.’

They each grabbed an arm and dragged the man down the hall. Bridie's face was lined with strain.

‘I can manage him,’ said Paddy, heaving one of the drunkard's arms over his shoulder. ‘Where do you want him?’

Bridie led the way into the parlour. She rolled out a thin flock mattress before the fireplace and Paddy dropped the visitor onto the bedding. Mum covered him up, wiping the tangle of curls away from his face with a tender gesture.

‘Is he your son?’

‘Not exactly. But he is my responsibility,’ she replied. For a moment she rested a hand on the sleeping man's shoulder and Paddy thought she looked more melancholy than anyone he'd ever seen.

After Bridie had gone back upstairs, Paddy settled down on the chaise longue. The air in the room was heavy with cigar smoke and whiskey, and the man was now snoring loudly. Paddy pulled his blanket up over his head and tried to pretend he was alone.

It too

k a long time for sleep to descend again and then his dreams were dark and troubled, as if a bitter new wind was blowing over the threshold of Charity House.

24

Ned Kelly by night

The next morning, Bridie sent Paddy down to the Princess Theatre with two hatboxes. By the time he returned, Eddie was sitting in the dining room hunched over a cup of muddy coffee.

Later, Paddy heard him arguing with Bridie in the front room, their voices rising and falling as if Eddie was angry and Bridie trying to placate him. Paddy thought he heard the chink of coins and then Eddie left the house, slamming the front door behind him. Paddy half-hoped that he wouldn't return but in the late afternoon he was back in the dining room, drinking whiskey from a tin cup.

‘Boy,’ he called, as Paddy tried to slip past him and out into the yard.

‘My name is Billy.’

Eddie put his feet up on one of the chairs and pointed at them. ‘these boots of mine need cleaning. Pull them off and give them a polish.’

Paddy glared at him. ‘there seems to be a misunderstanding,’ he said.

‘My understanding is that you are meant to earn your keep.’

‘I don't see what being your boot boy has to do with earning my keep.’

‘You polish old man Fox's boots and Flash Bill's, you can polish mine. And you'll address me as Mr Whiteley when you speak to me. Now remove my boots.’

Paddy stuck his hands in his pockets. Even if the man was a Whiteley, he was a bludger. ‘take them off yourself,’ he said.

For a moment they eyed each other angrily, and then Eddie laughed. He undid the buckles and threw his boots at Paddy.

‘Have them back to me in fifteen minutes, no more,’ said Eddie, taking another swig of his whiskey.

Resentfully, Paddy carried the muddy boots outside, slamming the door behind him.

That night, Paddy found Eddie asleep on the chaise longue. When Bridie saw Paddy standing in the parlour doorway, looking furious, she put a hand on his arm and gestured to the mattress on the floor.

‘I'm sorry, Billy,’ she said. ‘But Eddie's a bigger man than you and he's needing his rest. He's starting in a new role tomorrow.’

Paddy stretched out on the floor before the fireplace. When Eddie started snoring, Paddy imagined smothering the man with his own pillow.

Paddy couldn't understand why Mum turned a blind eye to all Eddie's bad behaviour. Any other lodger would have been turned out on their ear if Mum had caught them drinking whiskey in the middle of the day, but not Eddie.

When Wybert Fox vacated his room, Eddie took it over immediately. Paddy was sure he wasn't paying any board but the only person he could discuss it with was Nugget.

‘That sponger,’ said Nugget. ‘sucks the old lady for all she's worth, though he's not a bad actor. I heard he's taken over the lead in The Kelly Gang. I reckon I'll have to see it again now he's playing Ned.’

Mum was going to see The Kelly Gang too. It seemed everyone in Melbourne had seen the show. Paddy tried not to feel interested but on the evening that Bridie was to attend, he sat at the dining-room table, pushing his food around disconsolately.

‘It's the best play of the season,’ said Bridie. ‘I've heard they borrowed the iron armour that Kelly himself wore!’

‘It sounds grand,’ said Paddy.

‘I'm glad you say that, Paddy. Because if you don't mind accompanying an old woman, I'd like you to come along. I've already bought you a ticket.’

Paddy looked at her in surprise, and then hesitated. If only Eddie wasn't in the play, the treat would be perfect.

‘I'll get my cap,’ he said, and ran up to the front parlour.

Folded up neatly on the end of the chaise longue was a crisp white shirt, a pair of trousers and a smart new jacket. ‘I couldn't have you on my arm dressed like a street arab, could I?’ said Bridie, brushing away Paddy's thanks.

The Princess Theatre glowed like a fairy palace. The foyer was thronged with people in fine clothes while outside was a rowdy crowd with tickets for the upper circle. Paddy and Bridie took their seats in the stalls and Paddy looked around him in wonder. The red velvet curtains were trimmed with gold braid, and on either side of the stage, water cascaded over two small waterfalls. Beautiful women sat fanning themselves in the boxes. Above them, the chandeliers glittered in a haze of cigar smoke.

Paddy watched with amazement. On stage, Eddie was clear-eyed and powerfully impressive, nothing like the drunken good-for-nothing that Paddy knew him as. The whole audience was riveted.

At the end of the show, everyone leapt to their feet, including Paddy, applauding and whistling until the whole cast came to the front of the stage and took three curtain calls. Paddy forgot his animosity towards Eddie and clapped until his hands ached.

Outside, Bridie bought two slabs of dark fruitcake, and a cup of coffee for each of them.

‘One day, I'd like to be Ned Kelly,’ said Paddy. ‘I had a grandmother that was a Kelly, so I could call myself Patrick Kelly, or even Dan Kelly, because I'm Brendan too. And I could wear that armour and shoot the top off a bottle of whiskey, just like Eddie in the play.’

‘They tell a lot of stories about the bushrangers that make the life sound grand. But it's never a grand thing to have to kill for your living. I remember the day they hanged Ned Kelly. There were people weeping on the streets, but no one's tears could save him.’

‘Oh, I don't mean I want to be a bushranger, but I'd like to act at being one. Can you imagine anything grander? Eddie is so lucky.’

‘I'm sorry he never got a proper education. He could have been anything he wanted.’

‘Mum, why don't you like the theatre?’

Bridie laughed. ‘Billy, I love the theatre, it's been my life, but it's an easy world to fall in love with and a cruel trade to live by. I've seen great men end their days with nothing to show for years of hard work. I'm one of the lucky ones. There's always work backstage but since the crash there hasn't been much money in the theatre.

‘It's not like the old days. After the Star closed, that was our theatre in Ballarat, I came to Melbourne with the finest actress of her generation. Amaranta El'Orado, the Songbird of the South they called her. They were heady days. People had more money than sense! When we were at the Princess Theatre there'd be hundreds of miners throwing nuggets as big as walnuts onto the stage. I'd run out and gather them up and then Amy and I would put them in the safe. All that gold and all that splendour, all gone now.’

Bridie put her coffee cup back on the stall and gazed down Bourke Street with a faraway look in her eyes.

Paddy tried to imagine a stage littered with gold nuggets. But more exciting than the prospect of riches was the vision of a crowded theatre full of cheering people. He longed to be the person at centre stage. He had promised Violet that one day he'd be watching her from the front row of a theatre. How much better would it be if she returned to discover that Paddy had become Melbourne's idol, so that together they could bask in the limelight.

25

Where in the world

On a bright winter afternoon, Eddie came back early from the city and sat in the dining room with an open bottle of whiskey and a glass before him. Bridie loaded up a basket with jam and bread and tied her bonnet on.

‘Are you coming along then, Eddie?’

‘Not bloody likely. Don't think you can trick me into visiting that old witch again,’ he said.

‘She's been good to both of us, Eddie.’

‘Get that little bludger Nugget to go with you, if you want company. She's his grandmother, not mine.’

‘Never mind,’ said Bridie. She hoisted the basket onto her arm.

‘I'll come,’ said Paddy.

‘You don't even know where she's going!’ snorted Eddie. ‘then again, I suppose you're the sort that would find a lunatic asylum amusing.’

‘I like to help,’ said Paddy, picking up her basket. ‘Not like some.’

They took two trams, first the cable

tram and then one drawn by horses to the Princess Street hill in Kew. The Metropolitan Asylum for the Insane was a huge, ornate building, like a palace, with a great tower at each end rising above the surrounding bush.

‘It's so grand,’ said Paddy, wonderingly.

‘From the outside,’ said Bridie, ‘but God preserve us from ending up in such a place.’

The gatekeeper let them in, and they took the path up to the office. Paddy signed a leather-bound book with his own and Bridie's names, and they went through into an open quadrangle lined with long verandahs.

Bridie knocked on the door of one of the rooms before opening. Inside was dark and there were several beds along one wall. There was a constant drone from one of the patients, and Paddy felt his heart grow tight in his chest.

The woman in the bed was so withered and crone-like that Paddy could hardly believe that she was the same age as Bridie. Her pale blue eyes had a frost of white across the irises. She looked at Paddy, as he shifted the basket uncomfortably from one arm to the other.

‘Who's that? Is that your Tom you've brought, or is it his boy? Who is it, Bridie?’ she demanded.

‘No, Biddy. He's an orphan lad. Patrick Delaney, from County Clare. But we call him Billy.’

‘Handsome. You always have a handsome lad with you, Bridie.’

Just then, a nurse put her head around the door and gestured for Bridie to come and speak with her.

‘Where's she gone now, Eddie?’ said Biddy.

‘I'm not Eddie,’ said Paddy.

‘No, that Eddie's a scoundrel. Born a scoundrel,’ said Biddy, shaking her head knowingly. ‘You're not Nugget. Too handsome to be a Malloy. Maybe you're Brandon. Aye, that's who you must be, Brandon.’

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish Bridie's Fire

Bridie's Fire Vulture's Gate

Vulture's Gate The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie

The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie A Prayer for Blue Delaney

A Prayer for Blue Delaney The Year It All Ended

The Year It All Ended India Dark

India Dark Becoming Billy Dare

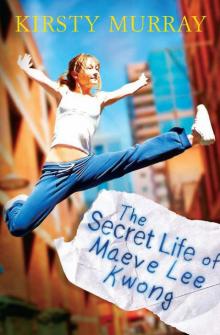

Becoming Billy Dare The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong

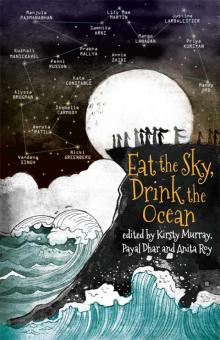

The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean