- Home

- Kirsty Murray

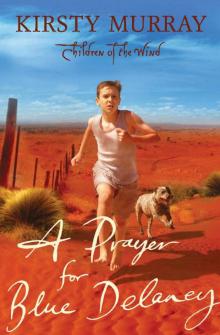

A Prayer for Blue Delaney

A Prayer for Blue Delaney Read online

The CHILDREN OF THE WIND quartet is a

sweeping Irish–Australian saga made up of Bridie’s

story, Paddy’s story, Colm’s story and Maeve’s story,

four inter-linked novels beginning with the 1850s

and moving right up to the present.

Bridie’s Fire

Becoming Billy Dare

A Prayer for Blue Delaney

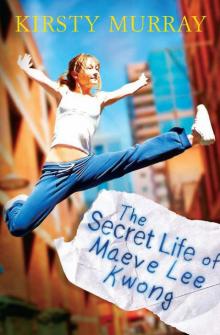

The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong

(forthcoming)

PRAISE FOR Bridie’s Fire

‘I loved it! Really, I couldn’t put it down. It’s such an

inspiration, your book is my favourite book in the world.’

Georgia, Year 8

PRAISE FOR Becoming Billy Dare

‘With every page you read, you feel as if you become

a part of Billy’s life!’ Stuart, 12

KIRSTY MURRAY is a fifth-generation Australian

whose ancestors came from Ireland, Scotland,

England and Germany. Some of their stories provided

her with the backcloth for the CHILDREN OF THE

WIND series. Kirsty lives in Melbourne with her

husband and a gang of teenagers.

OTHER BOOKS BY KIRSTY MURRAY

FICTION

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish

Market Blues

Walking Home with Marie-Claire

Children of the Wind

Bridie’s Fire

Becoming Billy Dare

NON-FICTION

Howard Florey, Miracle Maker

Tough Stuff

KIRSTY MURRAY

First published in 2005

Copyright © Kirsty Murray 2005

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Murray, Kirsty.

A prayer for Blue Delaney.

For children.

ISBN 978 1 86508 736 8

eISBN 978 1 74269 229 6

I. Title. (Series: Murray, Kirsty. Children of the wind; bk. 3).

A823.3

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth

Government through the Australia Council,

its arts funding and advisory body

Series designed by Ruth Grüner

Cover design and image by Pigs Might Fly

Set in 10.7 pt Sabon by Ruth Grüner

Teachers’ notes available from www.allenandunwin.com

Contents

Acknowledgements

1 A place in the sun

2 The luck of the Irish

3 The turning world

4 Dibs adrift

5 The first cut

6 Bindoon

7 The broken boy

8 Nothing to lose

9 Acts of faith

10 Haunting messengers

11 Bitter truth

12 The digger’s tale

13 Bush Christmas

14 Nugget on the goldfields

15 Seven sisters

16 Come in, spinner!

17 Stolen

18 The Dog Fence

19 Dare and McCabe

20 The letter

21 Into the flames

22 The Wolfram Queen

23 Unforgettable

24 Wild boar country

25 Dragon stone

26 Flying south

27 Answered prayers

28 Words and music

29 Waiting games

30 Sweet and sour

31 Reap the whirlwind

32 Faith, hope and glory

33 Goodbye to all that

34 Guarding the flame

35 Night of stars

36 Que sera sera

Author’s note

Acknowledgements

In researching the 1950s I was able to draw on the observations and reflections of countless friends and acquaintances. To those many people who enriched this story and whose names are not listed below, thank you.

I am especially grateful to the following people for their time, advice and inspiring suggestions: Lyn Ainslie, Mailee Clarke of the Fremantle Children’s Literature Centre, Henry Paterson Finch, Nano Finch, Peter Freund, Leigh Hobbs, Ruby Hunter, Gaye Lawrence of Green Valley - Pine Creek, Gladys Elsie Sumner, Ann Tregear, Helen Tregear, and Gabrielle Wang. Also thanks to Sarah Brenan, Eva Mills and Rosalind Price for their wise editorial guidance.

All historical fiction is built on a foundation firmly laid by other writers and historians. I would particularly like to acknowledge the works of Alan Gill and Barry Coldrey in making it possible for me to reconstruct the experiences of the boys of Clontarf and Bindoon.

Two separate Senate Committee inquiries produced reports that also assisted my research: Lost Innocents: Righting the Record, The Report of the National Inquiry into Child Migration and Bringing Them Home, The Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families. Both provided chilling factual information that influenced the creation of this novel.

David Unaipon’s Legendary Tales of the Australian Aborigines provided a source for the legend of the Mungingee. The Ngarrindjeri woman who befriends Colm, Doreen, is fictional, but the details of the dreaming she tells are true and belong to the Ngarrindjeri people.

Mayse Young’s autobiography, No Place for a Woman, and Barbara James’s history, No Man’s Land - Women of the Northern Territory, proved to be invaluable resources in writing the scenes set in Pine Creek. The Dog Fence by James Woodford provided many of the factual details incorporated into Colm and Bill’s journey. The fragments of poetry that Bill recites to Colm include William Butler Yeats’ ‘Easter 1916’ and Henry Lawson’s ‘The English Queen’.

For facilitating the research process, I would like to thank the Caroline Chisholm Library, the State Library of Victoria, Yarra Plenty Regional Libraries and the Performing Arts Museum, Melbourne.

I would also like to acknowledge the support of the Australia Council for their initial funding, without which I would never have dreamt of attempting this series.

And to my family - Ken Harper, Ruby, Billy and Elwyn Murray and Isobel, Romanie and Theo Harper - thanks for your enduring support. Three down, one to go!

For William Vyvyan Murray

and Rosalind Price

Because music, prayer and the written

word are all acts of faith

1

A place in the sun

Colm took the stairs two at a time, his feet pounding on the dark timber. At the top, he grabbed the balustrade, swung himself into the hall and slid wildly across worn floorboards. His chest ached from gasping air into his lungs. The nun was gaining on him, black robes billowing around her. Any moment now she’d swoop.

‘Colm McCabe, stop this instant.’ Her voice cut the air like shards

of glass.

But Colm didn’t stop. He kept running, running until the stairs ended and he was at the top of the building, with only the long, narrow fourth-floor hallway up ahead and nowhere left to turn. That’s where Sister Clothilde cornered him, at the end of the hallway next to the window, where he flattened his hands against the glass and screamed, ‘Mum! Mum! Mum!’

Far below, at the black cast-iron gates of the orphanage, his mother was pulling the latch shut. Red hair glinted in the morning sunlight, escaping from beneath her blue hat.

He could feel the nun’s breath as she grabbed his shoulder, trying to drag him away from the window.

‘Mum! Mum! Mum!’ he screamed, so loudly that the glass quivered. The orphanage echoed with his cries. Sister Clothilde wrestled him back along the hallway, hoisted him across her shoulder and carried him down the long stairs. When she reached the bottom and lowered him to the floor, Colm threw himself against the front door, screaming again for his mother. Someone grabbed him and stuffed something cold, damp and floury into his mouth. Colm tried to spit it out, but the nun put one hand under his chin and clamped his mouth shut.

‘Chew it!’

Colm gagged and tears sprang to his eyes. He was five years old. For the rest of his life, he could never eat potatoes without feeling the strangled cry for his mother that was stopped in his throat.

In winter there was only one small area of the schoolyard that sunlight could reach. High redbrick walls folded in on the yard and shadows lay like a damp blanket across the black bitumen. A patch of sunlight fell in a narrow triangle in the centre of the yard and the biggest boys always got to stand in it, their faces upturned to the light.

Colm leant against the wall, watching for his moment.

‘You’re not still waiting for a turn?’ asked Dibs McGinty. ‘How long you been here now, then? The whole bloody lunch hour. C’mon, McCabe. You must be sick of watching that scrap of sunshine by now. I won two new alleys off Blackwood and you weren’t even there to see.’

Colm shrugged and concentrated on willing the older boys to walk away. If he could make his thoughts sharp enough maybe they’d feel as if something was prodding them out of the light.

‘Are you even listening to me?’ asked Dibs. When Colm didn’t answer, he went on, ‘Now you was seven when I first met you and you was doing this back then. So that’s three years.’ Dibs counted on his fingers. ‘And then you was here for two years afore that. So five years, nearly every lunch hour, you’ve been standing, waiting for your turn. Ain’t you ever gonna give up?’

‘No, and you know why.’

Dibs shook his head. ‘Cracked.’

‘I have to do this. It’s important.’

‘You’re gonna cop it, McCabe. Just like last time. Don’t you never learn?’

The bell rang and Dibs ran to join the other kids streaming back into the building. But Colm wasn’t about to let go of this chance, after weeks without a sunny day. When the yard was empty, he ran to the patch of light and bathed his upturned face in the thin winter sunshine. Somewhere in England, that same sun was shining down on his mother. He remembered the day they’d gone to Brighton and sat side by side on the cold beach. Colm had picked up a pebble and flung it into the surf. He could still see the pebble arcing through the air and splashing into the sea, and the way the sun sparkled on the water. He could feel the warmth of his mother’s blue coat. It had a white fur collar. He remembered how it had tickled his cheek when she picked him up and hugged him, and how red her hair had looked against the soft fur.

Sister Clothilde came sweeping into the yard and grabbed him by the ear.

‘Late again, McCabe,’ she shouted. ‘Late again. I don’t want to hear any of that piffle about your mother and the sunshine. You know the punishment.’

Colm bit his lip, bitterly regretting having told Sister Clothilde any of his secrets. Very softly, beneath his breath, he started humming to himself, feeling the warmth of a song reverberating in his throat.

‘Stop that, this instant!’ said Sister Clothilde. She took Colm by the shoulders and turned him roughly to face her. Colm squirmed uncomfortably. He hated her face being so close to his.

‘You’d best be forgetting you ever had a mother. Do you think she thinks about you? Not likely. Not ever.’

‘That’s not true.’

‘Your mother is dead, or as good as dead to you, but you don’t seem able to get that into your thick skull. Since I can’t beat any sense into you, we’ll see if the boys can.’

Later that afternoon, Colm was made to stand at the foot of the stairs and take his punishment. All the other boys lined up as they came out of the dining hall, and as they passed him, each made a fist and punched Colm. There were seventy-six boys, but except for big Teddie Allsop, who didn’t know his own strength, every one of them pulled their punches short.

Out of the corner of his eye, Colm could see that Sister Clothilde was annoyed. The moment she unfolded her arms from across her chest, Colm knew what would come next. He shut his eyes and started humming beneath his breath, as if a song would hold off the moment. Sister Clothilde swept the other boys aside and bore down on him, her fist clenched hard, her knuckles white. She struck, and Colm’s neck snapped backwards, his head hitting the balustrade behind. He saw the folds of Sister’s habit swirling around him as he crumpled, felt the tang of blood in his mouth, and then the darkness swallowed him.

It took a week for Colm’s headaches to stop, and it rained the whole week. It was still raining on the day the three men came to St Bart’s.

‘What do you know about Australia, lads?’ asked a big red-faced man in a dark suit.

No one put up their hand.

‘Well, I’ll tell you about it. It’s a marvellous place. There’s kangaroos and horses to ride, and fruit simply falling from the trees. There are families that want boys like you, families with farms where they have their own milk and cream with breakfast every day. No one’s ever hungry in Australia. It’s a land of plenty and the sun shines every single day of the year. So now, who’d like to go to Australia?’

Dibs McGinty’s arm shot up. Dozens more followed.

Colm kept his hands folded in his lap. Dibs elbowed him sharply. ‘Don’t you want to get out of this place? Don’t you want to ride on a kangaroo?’

‘Don’t be daft,’ whispered Colm. ‘You can’t ride kangaroos.’

‘But we could get away from Sister Clothilde,’ said Dibs. ‘And we could have families. A real family. A mum, a dad. Maybe even brothers and sisters.’

But still Colm sat with his hands folded in his lap. One day his mother would come back for him and he was going to be waiting for her.

The next day, Sister Clothilde told Colm that he had been chosen.

‘Chosen?’ he repeated, looking at her blankly.

‘For Australia,’ she said, her lips pulled back over her teeth in the semblance of a smile. ‘Aren’t you lucky?’

‘I don’t want to go,’ said Colm.

‘Nonsense. Every boy wants to go. It will be like a grand holiday,’ she said, hurrying him outside and shutting the doors of the school behind him.

Colm found Dibs out in the yard. ‘I’m going to Australia too,’ he said, feeling dazed.

Dibs punched him in the arm. ‘Good-o. Maybe we’ll get adopted by the same family and then we’ll be like brothers.’

‘I’m not getting adopted. I’ve got a mother already.’

‘Well, I am. Then I’ll never have to go and live with my bloody uncle again. I’ll live in a proper house with a proper mum and dad.’

Colm smiled. Of course, Dibs couldn’t remember anything about his mum, so he had to dream of something better. The sun edged its way out from behind a bank of clouds, and Colm ran across the yard and bathed his face in the light.

2

The luck of the Irish

The photographer’s bulb flashed, and Colm blinked. Everything looked bright and strange - the long line of children t

ramping up the gangway, the swelling crowd on the docks, the steep, grey sides of the ocean liner. Beside him, boys and girls waved at the people on the dockside, though Colm was sure they knew no one down there. They were orphans from homes all over Britain.

Colm found himself standing amidst a group of boys with Irish accents. It made him think of music, the way the words seemed to roll off their tongues. They were bigger than Colm and they jostled each other, shouting and laughing as they pushed their way forward to the ship’s railing. Colm watched as the tallest of the Irish boys clambered onto the railing, clutching a post to steady himself. He was lean and wiry, with a shock of white-blonde hair that stuck up in tufts. His friends roared with approval as the boy leant forward and spat as far as he could into the milling crowd on the docks. He glanced back at his friends and laughed, before turning to send another gobbet of spittle into the crowd below. A steward yelled from further along the deck and pushed his way towards them. The tall boy turned to jump back on deck, but lost his balance. A collective gasp rose as he teetered on the railing, his arms flailing wildly. A woman screamed. Instinctively, Colm leapt forward, elbowing bodies aside to grab the boy by his shirt and pull him down. They hit the deck together, the big boy landing heavily on Colm, winding him.

The boy swore and quickly jumped to his feet. Colm tried to sit up but all he could do was cough and roll half onto his side as feet trampled in around him. Two hands reached down and pulled him up.

‘Youse saved me friggin’ life, you did,’ said the boy in a warm, lilting voice. ‘I’m Tommy. Tommy Cassidy from Belfast.’ He held his hand out for Colm to shake. The sun shone through his white-gold hair, making a halo of light around his head. Mutely, Colm put out his hand and felt the older boy’s sure, firm grasp. Before Colm could think of anything to say, the steward arrived and angrily wrenched Tommy away through the crowd. Tommy looked back, cockily raised one hand to salute and then winked.

The children ran along the decks, laughing and shouting, until three nuns came to herd them down to the dining room. Still feeling breathless, Colm slipped between two lifeboats and waited until everyone had gone below decks. When the coast was clear, he walked to the rail, watching England disappear from view. His ribs were aching and inside, he felt a new pain, as if something was being torn away from him as the distance from the shore grew further. He rested his forehead against the railing, humming softly to himself to fight down tears.

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish Bridie's Fire

Bridie's Fire Vulture's Gate

Vulture's Gate The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie

The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie A Prayer for Blue Delaney

A Prayer for Blue Delaney The Year It All Ended

The Year It All Ended India Dark

India Dark Becoming Billy Dare

Becoming Billy Dare The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong

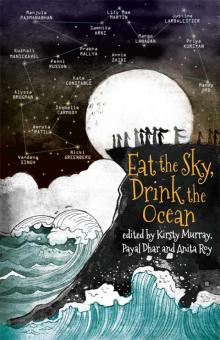

The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean