- Home

- Kirsty Murray

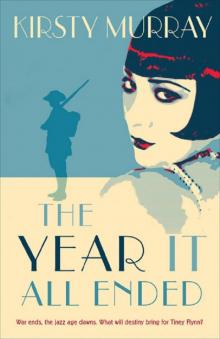

The Year It All Ended

The Year It All Ended Read online

KIRSTY MURRAY was born in Melbourne and lives there still, though she has tried on many other cities and countries for size. She has been a middle child in a family of seven children, a mother to three and stepmother to three more, as well as godmother and friend to many amazing people. She has loved books, stories and people all her life, and is the author of eleven novels.

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

First published in 2014

Copyright © Kirsty Murray 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from the National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 174331 941 3

eISBN 978 174343 881 7

Cover images: girl by Stevie McGlinchey, soldier by Ruth Grüner

Cover and text design by Ruth Grüner

To Julie Walker,

My Adelaide sister always

Contents

Before

Tears of peace

White feathers

The Cheer-Up Society

News from the Front

Winged letters

Inheritance

The McCaffreys return

Keeping promises

Cod’s heads and kerosene lamps

Voices of the dead

Hope tests its wings

Lost and found

Christie’s Beach

In the olive grove

Peace Day, 1919

Sunshine in the Riverina

Dream’s end

Barossa

Ready to fly

Blighty

On Beachy Head

Love’s memory

Fractured

Beneath the everlasting sky

Artists’ model

Langemarck

Butterfly kisses

Staircase to the moon

After

Tiney woke to the sound of voices drifting past her door. She slipped out of bed and tiptoed down the hall. Louis and Will stood by the woodstove in the kitchen, their faces lit by the flames that glowed in the open firebox. They were already dressed and Will had a bag slung across his shoulder. When they saw Tiney they grinned, their eyes shining in the gloom of the morning kitchen.

‘Where are you going so early?’ asked Tiney, rubbing sleep from her eyes.

‘To Glenelg,’ said Louis.

‘For a swim,’ said Will. ‘Do you want . . .’

‘. . . to come along?’ asked Louis.

Tiney felt breathless in their company. For a moment she couldn’t speak, glancing shyly from her big brother to her cousin. Louis and Will both had Wolfgang for their middle name, and ever since they were small everyone in their family had called the inseparable pair ‘the Wolfs’. One of Tiney’s very first memories was watching them wrestling on the back lawn, tumbling over each other like a pair of wolf cubs while she shrieked with excitement. In Tiney’s imagination, Louis, with his thick dark hair, was the black wolf while blond Will was the golden wolf.

‘How about it, little goose?’ said Will, not unkindly.

Louis reached out and tickled her under the chin. ‘She’s my littlest swan maiden, not a goose, aren’t you, Titch?’

Tiney slapped his hands away. ‘I’m not a goose or a swan, and you know they don’t let girls swim with boys at Glenelg Beach.’

‘Don’t worry, we’ll be too early for the warden. Hurry and grab your togs. We don’t want to miss a minute of sunshine.’

Tiney laughed and slipped quietly into her bedroom to dress, not wanting to wake her sisters.

The tram rattled down King William Street and on past Goodwood. Tiney sat between Louis and Will, dizzy with happiness to be allowed to be their mascot for the day. It was 1912. She was eleven years old.

The beach was dazzling; turquoise and blue water, white and gold sand with a few promenaders strolling along its length. The sea was calm and still, a mirror reflecting the morning sky. In the shadow of the long pier, Tiney changed into her woollen bathing costume and then skipped through the warm sand to where Louis and Will stood waiting for her, water lapping about their ankles. They wore identical black bathing suits though Will’s skin had a honey-gold glow from working in the vineyards while Louis was pale after a long winter of studying.

With Will on her left and Louis to her right, Tiney waded out into the cold waters of Holdfast Bay.

‘Race you to the deep,’ called Louis. He dove into the sea and Will plunged in beside him. A wave of icy water washed over Tiney.

‘Freezing!’ she shrieked.

Before she could let out another cry, the boys burst out of the sea and each grabbed one of Tiney’s arms. They swung her into the air, over the clear ocean, up and up. Tiney would never forget the feel of Will and Louis’ arms about her, the water rushing past her face, the sunlight cutting through the surface, the blue, blue sky above. She would hold the memory of the two young men, the air, the sky and the sea, like a perfect jewel of her childhood, for the rest of her life.

Tears of peace

On Tiney Flynn’s seventeenth birthday, every church bell in Adelaide tolled, as if heralding a new year, a new era. Tiney stood in the garden of Larksrest, purple jacaranda petals fluttering down around her, and thrilled to the tumbling waterfall of sound. One by one, her sisters came outside to join her; first Nette, then Minna and lastly Thea.

All those bells tolling, the shouts and engine whistles, the beating of drums and saucepans on a warm spring evening could mean only one thing. Peace. Peace swelling up above the town and spreading across a deepening blue sky to reach the four Flynn sisters, as they stood beneath a jacaranda tree holding hands, willing the war to be over.

‘Can it be true?’ asked Tiney.

‘The Kaiser’s already abdicated – you saw the pictures in this morning’s newspaper,’ said Nette. ‘It must be – peace at last.’

‘They’ve been talking about the Kaiser’s abdication for months,’ said Minna.

‘It could be a false alarm,’ said Thea. ‘We mustn’t get our hopes up – let’s not tell Mama, not yet.’

Nette laughed. ‘As if she can’t hear the bells! I’m going into town to find out everything. Right now. I won’t sleep a wink unless I know for sure. Let’s get our coats, Thea.’

‘Someone should stay with Mama,’ said Thea.

‘We’ll come!’ said Tiney. She grabbed Minna’s hand. ‘Won’t we, Min?’

‘Papa will be home any moment,’ said Nette. ‘And he’ll say you’re both too young to be out gallivanting and then he won’t let me out either. You all stay here, and I’ll bring back the news.’ She was already racing into the house to grab her hat and summer coat.

Tiney made to follow her. ‘Let her go,’ said Minna in a low voice. ‘We’ll take the bicycle. We’ll be in town before she climbs of

f the tram and home again before Pa notices we’re missing.’

The front door banged behind Nette as the others walked into the parlour. Minna bent down and kissed Mama on the cheek.

‘Tiney and I are going too, Mama,’ said Minna. ‘You won’t tell Papa, will you?’

Mama smiled and cupped her hands around Minna’s face. She could never say no to Minna. Tiney sometimes thought Minna was Mama and Papa’s favourite – for Mama, she was the daughter most like Papa, for Papa she was his wild Irish rose. Even when she was bad, even when they knew they should reprimand her, they couldn’t resist her smile.

Tiney wheeled the bicycle down the side path but when they were through the gate, Minna took charge.

‘Climb up behind me,’ she said, as she steadied the bicycle.

‘No! I want to sit on the handlebars so I can see everything. If you dink me on the back, I’ll have to peer around you,’ said Tiney.

‘Can you keep your balance all the way into the city?’

‘So long as you don’t get too tired pedalling!’

Minna settled herself on the leather seat. ‘Oh Tiney, you’re such a scrap of a kid. I could pedal to Melbourne and back with you on board.’

‘I might be small but I’m no baby,’ said Tiney. ‘Seventeen today!’

‘You’re still light as a feather. That’s all I meant,’ said Minna, pushing off from the kerb and sailing down the street.

As they turned the corner into Prospect Road, they dodged a brougham and two cars. The wind whipped Tiney’s plaits out behind her as Minna pedalled like fury.

‘Hold tight!’ cried Minna.

They whizzed past tramstops thick with people, past slow, plodding horse-drawn carts and footpaths crowded with pedestrians. Thousands of Adelaideans were being drawn by invisible threads into the heart of town to hear the news they’d been waiting for these last four long years.

The bicycle hurtled across the bridge over the Torrens and along King William Road, and then Minna steered it into the park. They bumped down the grassy bank of the river and skidded to a stop beside a rotunda. Tiney’s legs trembled as she jumped off the handlebars. Minna laughed and straightened Tiney’s hat and collar for her.

‘I probably look a sight myself, but you know, tonight I really don’t care,’ said Minna, smoothing out her skirts. Her cheeks were flushed, her hair windswept. She put a hand to her throat and laughed.

The two girls ran up to the road and locked arms as they made their way towards North Terrace, hurrying past the thick stream of people pouring into the city. Men and women shouted and yahooed all around them. Tiney and Minna were forced to stop as a procession passed by with three men on horseback and another young man carried high on the shoulders of merrymakers. Girls and young men marched along the street arm-in-arm, singing at the top of their voices while behind them a tin-can band made a racket and a woman stood on a corner weeping with joy.

‘Now my Jim will come back again,’ said a voice close behind Minna and Tiney. The sisters looked at each other at exactly the same moment. ‘And Louis,’ said Tiney. ‘Louis will come back to us.’

Louis had signed up in August 1914, within days of the war beginning. Mama wept but Papa was proud, and his sisters thought Louis in uniform was the handsomest man they’d ever set eyes upon.

There’d been many times when the family thought he was lost, long months where they had waited for any word from him. Then Louis had written in late August to say he was coming home. His division was about to be rested and would set sail from England in October. Just the thought of Louis walking through the front door of Larksrest again made Tiney let out a spontaneous whoop of joy.

Not far from Minna and Tiney stood two diggers in uniform. The taller, handsomer soldier called out to them, ‘It’s a beautiful evening for an armistice!’

Tiney wanted to ask whether they had been in France, like Louis, and how long it had taken for them to be demobbed, but Minna spoke first. ‘It’s the most beautiful evening of my life,’ she said.

The soldiers laughed. ‘The peace isn’t official yet.’

‘I’m sure the Premier will be here any minute to tell us it’s true,’ said Minna. ‘I feel so happy I could kiss someone!’

‘Right-o,’ said the soldier. And before Minna could object, he hooked his arm around her waist and drew her to him. Right there, while the crowds milled around them, Minna kissed him back. Tiney turned pink with embarrassment.

The second soldier looked at Tiney shyly. Tiney’s heart began to hammer so loudly she wondered if he could hear it too.

‘You’re just a kid,’ he said, as if to excuse himself from having to kiss her.

‘I’m seventeen,’ she said.

The soldier grinned. ‘Well, if you’re seventeen . . .’ He stepped closer, sweeping Tiney into his arms. She lowered her head, bumping her nose against his bright buttons. They both laughed at their clumsiness.

As the crowds surged forward, Tiney wriggled free of her soldier’s arms and grabbed Minna’s hand to make sure they weren’t separated as they wove their way onwards to the steps of Parliament.

It was 9.30 p.m. before the Premier arrived. Tiney stood on her tiptoes to see him but all he said was that there was no official news. If a statement from London arrived, it would be announced at noon on the morrow. The crowd let out a sigh of disappointment, but no one could shake the feeling that at any moment, peace would be upon them. Tiney and Minna wandered the streets, drinking in the waves of happiness that seemed to roll over the city. It was only when they heard the Town Hall clock strike 10.00 p.m. that they realised how late it had grown.

They pushed their way through the crowd and ran back to the river. As they stood on the bank of the Torrens, another roar went up from the crowds that thronged the city. Bugles sounded and songs of joy echoed along the river. Tiney and Minna hugged each other.

‘This is the best birthday of my life,’ said Tiney.

‘Peace, kisses, what more could a girl ask for?’ said Minna.

As Minna pushed the bike up the bank, Tiney asked, ‘Was that your first kiss?’

Minna laughed. ‘Ask me no secrets and I’ll tell you no lies.’

‘Minna!’

‘Was it your first kiss, sweet seventeen?’ asked Minna.

Tiney touched her face where the soldier’s buttons and rough wool jacket had grazed her cheek. ‘I didn’t let him kiss me.’

Minna screwed up her nose. ‘Aren’t you proper? Well, don’t you tell anyone about my kiss. Promise?’

‘I may be proper but I’m not a snitch. Of course I won’t tell.’

All the lights of Larksrest were aglow as Tiney flung open the front gate. For a moment, she stopped to admire her home; the golden sandstone cut square and smooth framed by neat red brickwork, with the four tall chimneys black against the night sky. The fanlight above the front door shone a welcome and the night air was full of the scent of spring. Tiney pulled down a branch of blossom and buried her face in the creamy petals.

‘I don’t think I’ve ever felt this happy,’ she said.

As they stepped onto the tiled verandah, Papa threw open the front door. For a minute, the girls braced themselves for his anger at their going out without permission and returning at such a late hour. But Papa was grinning. He picked Tiney up off her feet and whirled her around. ‘It’s the best news in the world, isn’t it, little one?’ he said.

Nette was already back from town, setting the table for supper and smiling. Everyone was smiling. Even Mama was humming to herself. The mood was only broken when Tiney said, ‘Do you think this means Will might come home too?’

No one spoke for a moment. Tiney winced, wishing she could swallow her words. Then Nette looked at Tiney sharply. ‘Cousin Wilhelm is a traitor, Tiney. Of course he can’t come home. He fought for the Germans. He might even have killed some of our boys.’

‘But he was one of our boys, once,’ said Tiney. ‘It wasn’t his fault that he was conscripted.’

>

‘He could have said he was a conscientious objector.’

‘In Germany? They would have shot him!’ said Tiney.

‘He’s still a traitor,’ said Nette, her cheeks reddening. ‘He shouldn’t have taken a German passport and Tante and Onkel should never have sent him to Heidelberg. There’s nothing wrong with the University of Adelaide. It was good enough for Louis. Wilhelm should have stayed at home. But he chose Germany, and if he’s dead it’s because of his family’s stupid ideas about Deutschtum.’

Mama put her hand over Nette’s and took the soup spoons from her tight clasp.

‘That’s enough,’ she said. ‘I will not have you talk of your cousin and your uncle and aunt like that, Annette. Everyone, please sit.’

They were all seated before anyone realised Thea was missing.

‘Where’s our Dorothea?’ asked Papa.

‘She’s in her cubby,’ said Mama.

‘It’s not a cubby any more, Mama, it’s a studio!’ said Minna.

‘I’ll fetch her,’ said Tiney, glad of an excuse to escape the dining table.

Through the paned window of the weatherboard shed at the back of the garden, Tiney saw Thea sitting on a stool, surrounded by her art materials: tins crammed full of brushes, neatly lined-up tubes of paint, a white china palette, a small folding easel. It wasn’t until she opened the door that she realised Thea was weeping.

‘Thea, what’s the matter? Are you feeling sad because you didn’t come into town?’

‘No, it’s not that. I didn’t want to go. I couldn’t bear to see people celebrating when the world we used to know, the world we grew up in, is so lost to us.’

‘But aren’t you glad the war is over?’

‘Of course I’m glad,’ said Thea, turning her tear-stained face towards Tiney. ‘I feel as if I’ve been holding my breath for four years, longing for it to end. But I can’t stop thinking of all those boys we grew up with – dead or broken. All the ones that will never come home.’

Tiney put her hands on Thea’s shoulders and turned her sister to face her.

‘Stop it, Thea,’ said Tiney. ‘You mustn’t talk like that. Louis is coming home, and Nette’s Ray, and George and Frank McCaffrey and thousands of other boys.’

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish Bridie's Fire

Bridie's Fire Vulture's Gate

Vulture's Gate The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie

The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie A Prayer for Blue Delaney

A Prayer for Blue Delaney The Year It All Ended

The Year It All Ended India Dark

India Dark Becoming Billy Dare

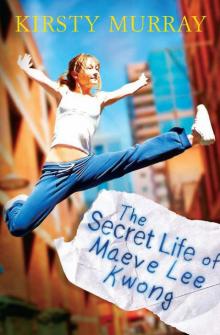

Becoming Billy Dare The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong

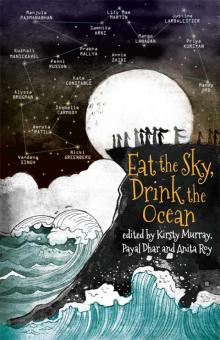

The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean