- Home

- Kirsty Murray

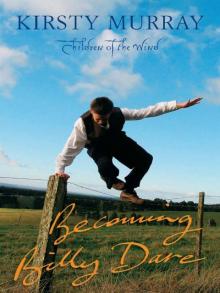

Becoming Billy Dare Page 13

Becoming Billy Dare Read online

Page 13

Paddy picked them up, shaking off the sand. Uncle Patrick's rosary beads.

‘They're mine,’ said Violet, pouting.

‘Do you even know what they are?’ said Paddy, furious. ‘do you know what this is?’ he asked, holding the tiny crucifix on the end of the rosary in front of her face.

‘He's my friend,’ replied Violet.

Paddy groaned. ‘Violet, these are special beads. They're for saying your prayers.’

‘Is prayers a game?’ she asked, curious, crawling through the sand towards Paddy and resting her elbow on his knee.

‘You know, praying. Like when you say your prayers before you go to sleep. Like the prayers your mam taught you.’

‘Mam didn't teach me no prayers. I don't know no prayers.’

The afternoon light cut through the pillars of the pier and lay warm on the sand. ‘You make like this,’ said Paddy, kneeling beside her. Then he took Violet's hands and pressed them together, wrapping the rosary beads around her fingers and thumb.

He taught her to say ‘Hail Mary’, feeling each line as a wound inside him and yet determined to teach her. She stumbled over the words to begin with, but soon caught the rhythm of the prayer. When she could recite it back to him, he crawled away from her, strangely exhausted. There was so much that she needed that Paddy couldn't give her.

The shadows grew longer and still they sat beneath the pier. Violet had put the rosary beads around her neck and gone back to making her castles in the sand. Paddy passed the pennies from one hand to the other, lost in thought. The tide moved up the beach and covered Violet's diggings, and the sun began to sink lower over the bay.

‘I've got a plan now, Violet,’ said Paddy, suddenly determined. ‘C'mon.’

‘Where are we going now?’ she asked.

‘You'll see.’

At an icecream cart in Bourke Street, just up from the Haymarket Theatre, Paddy bought a goblet of strawberry icecream with the last of the pennies. Violet's chin was quickly plastered with pink.

‘You'll have to be a bit tidier with your food once you're with the Lilliputians,’ said Paddy, wiping her face clean with the sleeve of his shirt.

‘So will you,’ said Violet, pointing to a smudge of icecream on Paddy's cheek.

Paddy looked away.

‘I'm not going, Vi,’ he said. ‘they didn't want me.’

‘Then I won't go either!’ she said adamantly. Paddy knelt down beside her.

‘No, Violet, you'll go. I've been thinking about it all day. You have to go. I can't take care of you any more and you wouldn't like it with the sisters at the convent. The theatre's the best place for you. You'll have a grand time of it. They'll take you to all sorts of beautiful places and you'll be the great star. When you come back to Melbourne, I'll be sitting right there in the front row and I'll be so proud. You want me to be proud of you, don't you?’

Her small face crumpled in distress. Tears streamed down her cheeks.

‘Will you stop that malarkey!’ he said crossly.

Violet flung her arms around his waist, clinging to him, refusing to be disentangled. ‘You said our mams wanted us to be together!’ she gasped through tears.

Paddy wrenched her arms free and held her wrists. He knelt down in front of her, staring hard into her tear-streaked face. ‘We will see each other again, one day. I promise. But I can't keep you with me now, Vi. Sweet Jesus, don't you understand? I would if I could. But the police will catch you and me too. They'll take you away and lock me up. They might even give you back to Jack Ace. You don't want that, do you?’

Violet blinked and then hiccuped. She shook her head, her black curls bouncing against her cheeks.

‘It's decided.’ He took her hand and led her into the theatre.

22

Beggarman, thief

Paddy stood on the corner of a city street, staring aimlessly at the passing crowd. He knew he'd done the right thing. He wanted to feel relieved that he didn't have to worry about taking care of Violet any more. But a cloud of misery gathered around him like a stifling cloak. In his mind's eye, he could see Violet, turning to wave as Mrs Pollard led her away and as she disappeared from view, what little brightness was left in his life was sucked away. All his thoughts seemed black, as if they were coated in thick sticky tar. He had no idea what to do next, no idea in which direction hope lay.

He didn't even notice Nugget Malloy sauntering up the street towards him.

‘You again,’ said Nugget. ‘Where's your midget? You ditch her?’

‘The Pollards took her,’ said Paddy flatly.

‘Blimey, that was a smart move. They give you anything for her? I heard they gave old lady Waites twenty quid for her pair of girls.’

‘I didn't want any blood money. They offered me five pounds but I didn't take it.’

Nugget laughed. ‘tiddler reckoned you was dumb but I didn't think you was that thick.’

‘Well, maybe I'm not as smart as you, Nugget. What do you do to earn your keep?’

‘This and that,’ said Nugget evasively. ‘It's been bad around Melbourne for years. I flog race cards, matches, get a bit of work here and there.’

‘I need to find work,’ said Paddy. ‘something, anything.’

Nugget shifted uncomfortably from foot to foot, as uneasy talking about employment as if it were an unsavoury disease.

‘You can't be worrying about the future when it's Saturday night in town. Bourke Street, that's the place to be. Tiddler and some of me other mates should be working the street by now.’

‘Do they sell matches too?’ asked Paddy.

‘They keep themselves busy,’ said Nugget.

Bourke Street was crowded. The coffee palaces were full and long lines of cabs crowded the streets as people spilled out of the theatres. Nugget wove his way confidently through the throng with Paddy close behind.

At the top of the street, Paddy saw Nugget slip his hand into an elegant young man's coat pocket. The movement was so slight, so deft, that Paddy thought maybe he was mistaken until he saw Nugget tuck a wallet into the back of his trousers. He grabbed Nugget's arm.

‘What are you doing?’ he whispered angrily. He snatched at the wallet, determined to return it, when suddenly someone grabbed him by the back of his shirt, lifting him right off his feet.

‘Damn pickpockets,’ said the man, wresting the wallet from Paddy. ‘I'm sick to bloody death of you lot.’

‘Wait, Eddie,’ said a calm voice. ‘I think you've caught the wrong one.’

The old woman who had spoken was holding Nugget by his ear. She obviously had a firm grip, because Nugget was wincing.

‘Now then, Nugget Malloy, what do you think you were doing, having a blind stab at Eddie?’

Paddy was amazed to see Nugget blush.

‘It wasn't me,’ said Nugget. ‘You got the wrong boy’

The old woman glanced sharply at Paddy, taking the measure of him. Then she turned back to Nugget, took him by the collar and shook him like a cat.

‘I don't reckon he looks like a ripperty man,’ she said, ‘though if he spends enough time with you, Nugget Malloy, he's bound to take to thieving.’

‘He was the one holding the wallet, wasn't he?’

Paddy flushed with anger. ‘I was going to give it back.’

The old woman laughed and gave Nugget one last shake. ‘Now, don't you try your nonsense around me, Nugget Malloy. I know you too well. You understand? You're lucky Eddie didn't set the coppers on you.’

Eddie snorted and turned to the old woman.

‘You're wasting your time talking to this pair of scoundrels, Mum.’ Eddie lowered his voice. ‘Can you stake me that few shillings?’

She opened a small black change purse and extracted the coins. As soon as he had the money, Eddie quickly disappeared into the theatre. The old woman turned back to Nugget.

‘And here's two bob for you, too,’ she said, handing the coins to Nugget. ‘You make sure you spend it on tucker and not smoke

s or two-up, understand? And you keep your paws off this innocent. I'd take his word above yours and if you try turning him to the bad, you'll have me to answer to.’

Nugget glanced sullenly at Paddy. ‘I didn't know you was already a friend of Mum's,’ he said, accusingly. Then he turned and ran off. Paddy fought down an urge to run after him.

‘Thank you,’ said Paddy. ‘I appreciate your help but I can look after myself.’

‘I wasn't doing it for you. Someone's got to talk sense to that Nugget. He's going to end up in jail if he's not careful, just like his father,’ said the woman, watching Nugget disappear. Then she turned her attention back to Paddy.

‘Mrs Bridie Whiteley,’ she said. When she smiled, her green eyes were surrounded by a pattern of deep lines and Paddy noticed a long scar, like a lightning bolt, that ran the length of her face, but her expression was kindly.

‘Billy Smith,’ said Paddy.

‘Smith? But there's no mistaking that accent. You're not from County Kerry, now are you?’

Paddy shook his head.

‘And tell me then, who's been laying into you, Billy?’ she asked, putting one hand gently under his chin and turning his face upwards.

‘It's nothing,’ said Paddy, embarrassed.

‘Why aren't you at home? Are you frightened that your mum or dad will take you to task for scrapping?’

Paddy didn't answer.

‘You're on your own, aren't you?’

Suddenly, Paddy felt misery wash over him like a great wave. He nodded wearily. As if she read his thoughts, the old lady hooked one arm under his and led him up the street.

‘It's not far to my place, but the tram's a nicer ride,’ she said.

She paid his fare and they sat in the open section of the carriage.

‘Here we are, love,’ she said, as the tram stopped alongside a bluestone cathedral. 'my house is around the corner from here.’

Paddy followed her into a narrow street lined with terrace houses. The name of each building was etched in fine lettering in the fanlights above the door: Constance, Alice, Emily. Finally they turned up the steps of the last house, Charity House. The old woman led Paddy upstairs to a small bedroom at the back of the building. A thick red rug covered the floorboards and every wall was lined with pictures. Beneath the window was a narrow cast-iron bed with a beautifully embroidered coverlet. Blossoms lay scattered across the windowsill of the room. For a moment, Paddy thought of Violet. If she'd been with him, she would have gathered them up in her hands. He wondered where she was sleeping tonight, if the Pollards had a nice bed for her or if they'd gone straight down to the wharves and slept on the boat that would take her to New Zealand.

‘You look done in, lad,’ the old lady said, pouring some water from a jug into a basin on the washstand. ‘You clean yourself up a bit and then come downstairs for some tucker.’

The water was cold and the soap smelt sharply of lye. Even so, Paddy had never imagined that washing his face and hands could feel so good. Though his bruises were tender, it was a relief to wash away the dirt, salt water and dried blood.

After the noise and bustle of the city streets, the quiet of this room was like a haven. He lay down on the bed and wondered where he would sleep the night. Wherever that was going to be, he knew one thing for sure. Tomorrow morning there would be no arms wrapped tight around his chest, no head on his shoulder. No Violet. He shut his eyes, trying to drive away the thought of her.

23

Fire and gold

Morning sun dappled the bedroom floor. Paddy sat up with a start and saw the old woman standing by the window, sweeping the blossoms from the sill.

‘I'm sorry, ma'am, I only lay down for a minute and then …’

The old lady turned and smiled at him. ‘You must call me Mum. All the young ones do. And never you mind about the bed. Often as not, I fall asleep in my chair when I'm stitching late at night, so I didn't miss it.’ She scattered dry breadcrumbs in place of the blossoms. In a moment, there was a rush of wings as birds came fluttering in to land on the sill.

‘Do you like birds?’ asked Paddy.

‘I cannot bear to see any living creature go hungry,’ she said. ‘so you must come and have some breakfast.’

Paddy splashed his face with fresh water and padded down the stairs in his bare feet. On the landing, he met a small elderly man in a striped suit. The man wore a blue silk cravat and had a stiffly waxed moustache.

‘Are you another one of Bridie's street arabs?’ he asked.

‘I don't think so, sir,’ answered Paddy.

‘Good-o. That last one was a right little devil,’ he said. He pinched the end of his moustache and stared disapprovingly at Paddy's bruises. Paddy smiled nervously and then hurried down the stairs.

A big black pot of porridge sat on a trivet in the centre of the dining table. The old lady was setting places around it for a number of people. A small fire burnt in the grate, even though the morning wasn't cold, and the room was bright with morning sunlight.

‘Do you take in lots of street arabs?’ asked Paddy.

‘I help those I can when I can, but I have to earn my living. This place may be called Charity House but it's a fine lodgings for actors, not a boys' home.’

‘A man on the stairs said something about the last boy being a devil.’

Bridie laughed. ‘that was old Wybert Fox and you know the devil he was speaking of well enough. Nugget Malloy. I've a soft spot for the boy on account of his grandmother being my old friend. But he pinched Wybert's snuff and pawned his watch, so I had to have stern words with him. He's like his grandmother, bless her soul, and doesn't take kindly to playing by the rules.’

‘I noticed that,’ said Paddy. ‘do you have many guests?’

‘There's always a passing parade of lodgers. Upstairs at the moment, I've got the Tallis twins, Lulu and Millie. They've got the balcony room. Lovely girls, used to dance with the Butterfly Brigade but they've got their own act now, fronting all the Bijou ballerinas. Wybert Fox has the other upstairs room. He's a grand old figure. Been here the longest, nearly a year now, but his show's doing so well he'll be off to Sydney for a season. Theatre folk are hard to keep in one place. Flash Bill Hurley's got the downstairs room. Have to put him at a bit of a distance from the girls, he's always after a bit of mischief, the rascal. They all like it here, only ten minutes walk down to the theatres and they know I keep a clean house with good fare.’

Paddy liked the warmth in the old lady's voice and the way she smiled as she spoke. He wished he had enough money to pay for a few nights lodging.

‘Nugget, he was going to bring me up here when I first arrived in town, to see if you had a spare room. But that was before I lost all my money.’

‘He didn't take you down to John Deary's two-up rooms, did he?’ asked Bridie, crossly.

Paddy laughed. ‘No, but I wish he had. I couldn't go because …’ Paddy trailed off, thinking of Violet.

Bridie looked at him curiously and then poured them each a cup of tea.

‘Billy?’ she said, gently.

Paddy started, forgetting he had told her that was his name.

‘It's not my real name,’ said Paddy. He took a deep breath as he tried to think up an explanation but instead, the whole story came out, from leaving the Burren, running away from St Columcille's, the wreck of the Lapwing, to the circus, finding Violet and leaving Gunyah Station. When he told her of handing Violet over to the Pollards, his voice caught.

‘Perhaps it's worked out for the best,’ said Bridie, shaking her head.

‘How can it be for the best?’

‘A boy like you would be wasted in the Lilliputians. You can already read and write. You could get yourself a position as a clerk, work your way up. A real job with steady pay. You don't want to get yourself mixed up with a bunch of ragbag actors. Maybe you could study in the evenings at the University, become a lawyer or a fine scholar.’

Paddy laughed. ‘studying? I've no money, no

home, no work, no family – nothing! If only the Lilliputians had let me waste my time with them!’

Bridie shot him a curious look and Paddy was worried that she was offended. She pushed her chair away from the table and picked up the teapot.

‘You bring your bowl out to the kitchen when you're finished,’ she called over her shoulder.

Paddy licked the last of the porridge from the dish and followed her into the back yard. A corrugated iron lean-to stretched along one side, and inside it, Bridie was cooking bacon and eggs on a range.

Paddy put his bowl down beside the trough.

‘Thank you kindly, ma'am. I'd best be getting on my way. I'm hoping to find some honest work today.’

Bridie turned to Paddy. ‘Billy or Patrick? Which is it to be?’

‘Billy,’ said Paddy, decisively. ‘I don't feel as if I'm Paddy Delaney any more. I need to start all over again.’

‘Well, Billy, I've a lot of work on at the moment, getting everyone ready for the Christmas pantomimes. See, I work on costumes as well as running the boarding house. I have a girl to help with the cleaning but I could use an extra pair of hands, to do chores and run errands for me. I can't be paying you but I'll feed you well and keep you warm and dry and slip you the odd sixpence when I can spare it.’

‘You're offering me work?’

Bridie laughed. ‘Just your lodgings in exchange for this and that, until you find your feet.’

‘I'm not like Nugget,’ said Paddy. ‘You won't be sorry.’

‘I saw that the moment I set eyes on you,’ she said.

She handed him a small axe and Paddy spent the morning splitting kindling for the range and stacking wood in the narrow yard. In the afternoon, Bridie sent him to the shops in Brunswick Street, to buy the newspaper and items that the lodgers had asked for – hair wax for Flash Bill, snuff for Wybert Fox and throat lozenges for the Misses Tallis.

That evening, Bridie made up a bed for him on a red chaise longue that stood under the window in the front parlour of the terrace house. It wasn't really used as a parlour at all. Bolts of fabric were piled up on shelves either side of the fireplace and a sewing table with a treadle machine was set against one wall. A long trestle table with lengths of cloth draped across it served as a work bench, and a wooden cabinet opened to reveal dozens of little drawers, each one full of haberdashery: ribbons and buttons, fasteners and lace.

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish Bridie's Fire

Bridie's Fire Vulture's Gate

Vulture's Gate The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie

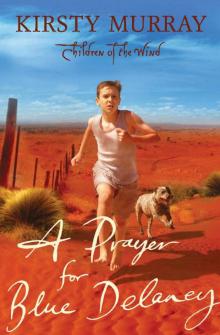

The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie A Prayer for Blue Delaney

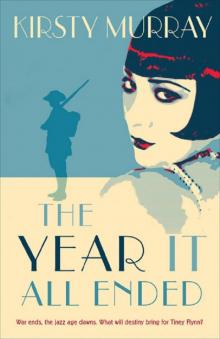

A Prayer for Blue Delaney The Year It All Ended

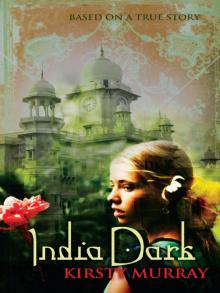

The Year It All Ended India Dark

India Dark Becoming Billy Dare

Becoming Billy Dare The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong

The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean