- Home

- Kirsty Murray

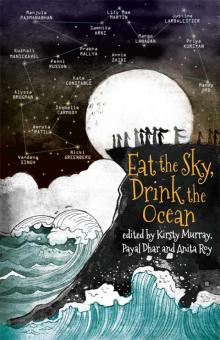

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean Read online

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean

Be transported into dystopian cities and alternate universes. Hang out with unicorns, cyborgs and pixies. Learn how to waltz in outer space. Be amazed and beguiled by a fairy tale with an unexpected twist, a futuristic take on a TV cooking show, and a playscript with tentacles. In other words, get ready for a wild ride!

This collection of sci-fi and fantasy writing, including six graphic stories, showcases twenty of the most exciting writers and artists from India and Australia, in an all-female, all-star line-up!

About the Editors

KIRSTY MURRAY is one of Australia’s most popular authors for children and young adults. Her novels include The Lilliputians also published by Young Zubaan.

PAYAL DHAR has written five books, including the Shadow in Eternity trilogy for Young Zubaan, as well as numerous short stories.

ANITA ROY is a writer, editor and columnist with over 25 years publishing experience in the UK and India. She heads the Young Zubaan list, and has recently completed her first novel for children.

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

First published in 2014

Copyright © in this collection, Payal Dhar, Kirsty Murray and Anita Roy (eds), 2014

‘Swallow the Moon’ copyright (text) © Kate Constable, 2014; copyright (illustrations)

© Priya Kuriyan, 2014

‘Little Red Suit’ copyright © Justine Larbalestier, 2014

‘Cooking Time’ copyright © Anita Roy, 2014

‘Anarkali’ copyright (text) © Annie Zaidi, 2014; copyright (illustrations) © Mandy Ord, 2014

‘Cast Out’ copyright © Samhita Arni, 2014

‘Weft’ copyright © Alyssa Brugman, 2014

‘The Wednesday Room’ copyright (text) © Kuzhali Manickavel, 2014; copyright (illustrations)

© Lily Mae Martin, 2014

‘Cat Calls’ copyright © Margo Lanagan, 2014

‘Cool’ copyright © Manjula Padmanabhan, 2014

‘Appetite’ copyright © Amruta Patil, 2014

‘Mirror Perfect’ copyright © Kirsty Murray, 2014

‘Arctic Light’ copyright © Vandana Singh, 2014

‘The Runners’ copyright (text) © Isobelle Carmody, 2014; copyright (illustrations)

© Prabha Mallya, 2014

‘The Blooming’ copyright © Kirsty Murray and Manjula Padmanabhan, 2014

‘What a Stone Can’t Feel’ copyright © Penni Russon, 2014

‘Memory Lace’ copyright © Payal Dhar, 2014

‘Backstage Pass’ copyright © Nicki Greenberg, 2014

All rights reserved.

Young Zubaan

an imprint of Zubaan Publishers Pvt. Ltd.,

128b Shahpur Jat, First Floor,

New Delhi 110049, India

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.zubaanbooks.com

eBook ISBN: 9789383074990

Print source ISBN: 9789383074853

This eBook is DRM-free.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Zubaan is an independent feminist publishing house based in New Delhi with a strong academic and general list. It was set up as an imprint of India’s first feminist publishing house, Kali for Women, and carries forward Kali’s tradition of publishing world quality books to high editorial and production standards. Zubaan means tongue, voice, language, in Hindustani. Zubaan is a non-profit publisher, working in the areas of the humanities, social sciences, as well as in fiction, general non-fiction, and books for children and young adults under its Young Zubaan imprint.

Cover and text design by Sandra Nobes

Cover illustration by Priya Kuriyan

Printed by XXX

Hello Reader!

This is just a note to let you know that all Zubaan ebooks are completely free of digital rights management (that is, DRM-free), so that you can read them on any of your devices and download them multiple times. We believe that this makes for a more trouble-free and pleasurable reading experience. To be fair to our authors and to enable us to continue publishing and disseminating their work, we appeal to you to buy copies of this ebook rather than share or give it away free. Thank you for your support and cooperation. And happy reading!

Contents

Cover

About the Book

About the Editors

Title Page

Copyright

Note to the Reader

Introduction

Swallow the Moon Kate Constable and Priya Kuriyan

Little Red Suit Justine Larbalestier

Cooking Time Anita Roy

Anarkali Annie Zaidi and Mandy Ord

Cast Out Samhita Arni

Weft Alyssa Brugman

The Wednesday Room Kuzhali Manickavel and Lily Mae Martin

Cat Calls Margo Lanagan

Cool Manjula Padmanabhan

Appetite Amruta Patil

Mirror Perfect Kirsty Murray

Arctic Light Vandana Singh

The Runners Isobelle Carmody and Prabha Mallya

The Blooming Manjula Padmanabhan and Kirsty Murray

What a Stone Can't Feel Penni Russon

Memory Lace Payal Dhar

Back Stage Pass Nicki Greenberg

Notes on the Collaborations

About the Contributors

Introduction

In late 2012, Australia and India were rocked by violent crimes against young women. In Delhi, thousands pro-tested against rape. In Melbourne, thousands stood vigil in memory of a young woman raped and murdered while walking home. The fate of all young women, what they should fear and what they can hope for were hot topics in the media around the world. Out of that storm rose the idea for this anthology.

We decided on the title Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean because it suggested impossibilities, dreams, ambitions and a connection to something larger than humanity alone. It was inspired, in part, by a 1930s labour song in which bosses and priests tell workers that ‘You won’t get to eat pie until you’re in the sky’ (i.e., until you’re dead). ‘Pie in the sky’ has come to mean any kind of wishful thinking – something you can’t have in this lifetime.

This collection of stories embraces the idea of not just eating pie but of taking big, hungry mouthfuls of life and embracing the world. It’s about the desire to have and do impossible things, especially things that girls aren’t meant to do. We asked our contributors to re-imagine the world, to mess with the boundaries of the possible and the probable.

Then we threw them another challenge. They were to work their magic in collaboration with a partner from the other country. Over Skype and email they shared stories about the challenges of being a girl or woman, and speculated how the world could be otherwise. Our cross-border confabulations produced seventeen works of fiction – six graphic stories, one playscript and ten short stories. In this collection you will find dystopian worlds and distant galaxies; alternative histories and time travel; fairy tales with a twist – and even a Shakespeare spin-off. You’d imagine a speculative feminist collection to be full of stories about strong and fantastic girls vaulting over traditional role barriers – but many of the stories are just as much about boys.

Some pairs worked together to craft a single piece of work, while others chose to bat ideas at each other and then work independently on a common theme. The notes at the end of the volume narrate their individual journeys; among the most interesting are the writer–illustrator pairs that starte

d off sceptical and ended up sold on the idea of collaboration.

We wanted contributors to be bold, so we encouraged them to go beyond the expectations of their cultures, and to think not just about their own realities but also those of young adults, who may be like or unlike them. It was incredibly exciting to see people separated by thousands of kilometres sharing ideas about what it means to be human, to love and to live in this world. Unexpectedly, a strange synchronicity came into play. It was as if, unconsciously, the imaginations of all twenty artists and writers became interconnected.

Ultimately, this is a book about connections – between Australia and India, between men and women, between the past, the present, the future and the planet that we all share. If we had to name one thing we learnt in the process of making this anthology, it’s the fact that when you eat the sky and drink the ocean, you are part of the earth: everything’s connected.

Little Red Suit

Justine Larbalestier

For my favourite engineer, Varian Johnson

You’ve heard this story. Only this time she didn’t meet a wolf in the woods. There were no woods, no wolves.

Besides, everyone knows men are worse than wolves. Sharper teeth too.

The only thing that was the same was the redness: the suit she wore was scarlet.

The knife she wielded was sharp.

Her name was Poppy.

Poppy was fifteen years old and had never seen rain. The drought began six years before her birth. The longest on record.

She was born in Sydney, that city of fewer than fifty thousand souls existing in protective suits underground, beneath precarious shielding, on islands that had once, before the seas rose, been part of the mainland. The city had had seasons once. Now it was drought for years and years, or floods and then years of drought again.

So many years that Poppy didn’t quite believe in rain.

Her Grandma Lily refused to live in the city. She was one of the folk who lived in sealed homes outside the city. She contributed to the city and in turn the city supported her. Every year there were fewer like her.

Grandma refused to move from the home that had been the family’s since the 1880s, when trees could live outside, and sun and wind and rain didn’t kill everything.

Killed almost everything, but not hard-shelled insects, not bacteria.

Her grandmother said she could fix what needed fixing. She was an engineer. The shielding had mostly failed, the neighbourhood been abandoned; Grandma’s house, even with all her fixes, would be uninhabitable soon.

Grandma Lily hadn’t replied to Poppy’s last message. But Grandma often skipped mail for days, saving electricity to reduce the heat.

Poppy knew she was alive, but her mum had decided Grandma was gone. Poppy closed her eyes, breathed deep, let a tear roll down her cheek, before the moisture was reabsorbed into her suit with only a trace of salt left.

Poppy’s mum didn’t understand Grandma Lily; she wasn’t an engineer. But Poppy and her grandmother were the same kind: she was going to be an engineer too.

She messaged Grandma Lily again.

Poppy was desperate to see her, desperate, too, to get out of the city, where she lived pressed too close to people whose faces she’d tired of. Poppy wanted to walk without being jostled, propositioned or pawed – it was always the same creeps, the unassailable doctors, teachers, lordly engineers – or admonished, or given work she didn’t want to do, or lectures on how they had to pull together if she showed any reluctance to do that random work.

She was sick of the two-metre-by-two-metre room she shared with her mother, where it was hard not to think of the tonnes of earth, and concrete, and other people’s homes pressing down on her. Where the walls were so thin that signing was the only way to communicate privately.

She wanted to see the moon and the stars through less than six or seven layers.

If Poppy couldn’t escape – even for a day – she’d explode.

There was no prison in the city. If you ran amok you were put outside, without a suit. Two weeks ago an engineer had tried to force himself on an apprentice, not caring that there were dozens of witnesses. The city put him outside.

No one left the city alone on foot unless it was punishment. Or suicide. There were rumours of people living out there wild. Poppy didn’t believe it.

She would have to walk to her grandmother’s. They couldn’t afford to hire a car, and public transport only ran during the day. All battery-stored energy was saved for hospitals and lowering the temperature at night.

Solar and wind power was all there was.

There and back was only a two-hour journey. She had done it before with her mum.

This time her mum would not join her.

They fought.

Her mother tried to reason with her, tried blackmail, threats. She didn’t raise her voice. No one ever did; eventually the ones who yelled walked out of the city without a suit.

Her Uncle Jon wished to see her. Poppy shook her head.

We owe him, her mother signed.

No, you owe him, Poppy didn’t sign.

Her mother’s best friend, Ana, nodded. It’s politic to see him.

Poppy felt the weight of their disapproval.

Their suits hung from pegs on the wall. Ana’s was yellow. The new suits were yellow or white or silver, to reflect light, not absorb it. Imported from India. Everything good came from there or the Americas.

Poppy went to see him. He wasn’t her real uncle. Her mother and he had been friends when they were little. Then he became an engineer; she didn’t. Her mother owed him and owed him until now he owned her.

But he doesn’t own me, Poppy also didn’t sign. No one was ever going to own her.

She agreed to meet him in Whitlam Square with her suit on and hundreds jostling them. The shielding there was good – eight layers – the air mostly breathable.

He was on the Council. A respected man. A popular, handsome man. Everyone said so. Everyone nodded and smiled at him as they went by.

Poppy and Uncle Jon unsealed their visors so they could speak unmonitored. Signing wasn’t private in public. Uncle Jon’s suit was silver; the most expensive kind.

‘There are monsters out there,’ he said. She could barely hear him over the crowd. She did not lean closer.

‘I’ll be careful,’ Poppy said, not believing him. Nothing could live out there, not without a suit, not without support from the city.

‘You might not come back,’ he said, sealing his visor, walking away.

She wondered why anyone thought him handsome.

Even Poppy’s best friend, Umami, thought she was an idiot.

Not that I don’t long to be somewhere else. But there is nowhere else. Until we’re engineers. It’s the only here we’ve got.

Umami was an apprentice too. It was what anyone smart did.

Leaving the city alone on foot, even in a suit, was not.

They sat on top of the craft hall, in their suits – Umami’s was green, old, but not so old as Poppy’s – looking east at what had been Sydney. Most of it under water, except these few islands. Her grandmother on one of the closer ones.

They weren’t alone – they were never alone – but there were fewer people on this roof. Unbreathable air.

Is that a crack? Umami pointed to a fissure forming in the shielding.

Poppy nodded. There were too many cracks. Umami signed that she was reporting it. It would be added to the list.

They might not let you go.

I’m fifteen. They have to.

We’ll get to the Americas, or India, Umami signed.

The only places you could walk outside at night without a suit.

You and me. We’ll sit their exams and they’ll whisk us away.

It had been years since anyone from Sydney had managed it. Uncle Jon had failed five times.

; I’ll be a chemical engineer and you mechanical.

In the city, engineers didn’t specialise. They had to do everything; so nothing was done well. Grandma Lily’s words, but Poppy knew it was true.

Did you hear some of the engineers have been getting exiled on purpose? They’re building a secret city.

I roll my eyes, Poppy signed, without actually rolling them. Those rumours had been around for years. Umami believed the most unlikely tales. Can you imagine? All those nasties building a hidden city? They’d kill each other in a week.

I guess, Umami signed. Be careful.

Everyone knew everyone’s business. They flicked their hands in disapproval when Poppy passed them in the halls. She stopped taking calls. She was fifteen; she didn’t need permission.

Out loud her mother said, ‘You are reckless. You are wrong.’

They always signed. Poppy could hear the neighbours agreeing. They, too, wanted everyone to hear.

Her mother’s words made her stomach tight.

Then her mother turned her back, did not sign, or say, another word.

Three days of silence.

Poppy felt cold.

She left without her mother’s approval.

Poppy stepped through the final seal of the city, as the last traces of sun disappeared, leaving behind disapproving looks, people pressed too close. She crossed the cleared perimeter quickly – it felt too exposed – much better to be in the remains of the old city, amidst semi-fossilised trees, crumbling buildings, and piles of rubble.

She walked along with her arms stretched out, not touching anyone. She couldn’t see anyone. Poppy smiled.

Once it had been a tree-lined street. She’d never seen it that way, nor had her grandmother, yet Poppy knew how it had been. Everyone did. The city was dedicated to keeping memories of the old city alive.

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish Bridie's Fire

Bridie's Fire Vulture's Gate

Vulture's Gate The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie

The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie A Prayer for Blue Delaney

A Prayer for Blue Delaney The Year It All Ended

The Year It All Ended India Dark

India Dark Becoming Billy Dare

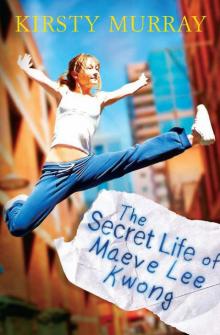

Becoming Billy Dare The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong

The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean