- Home

- Kirsty Murray

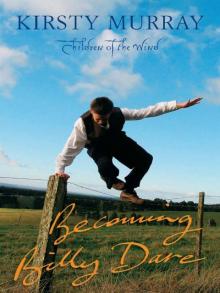

Becoming Billy Dare

Becoming Billy Dare Read online

The CHILDREN OF THE WIND quartet is a sweeping Irish-Australian saga made up of Bridie's story, Patrick's story, Colm's story and Maeve's story, four inter-linked novels beginning with the 1850s and moving right up to the present. The first in the series, Bridie's Fire, was published in 2003.

Bridie's Fire

Becoming Billy Dare

A Prayer for Blue Delaney

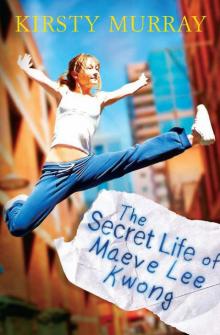

The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong

KIRSTY MURRAY is a fifth-generation Australian whose ancestors came from Ireland, Scotland, England and Germany. Some of their stories provided her with the backcloth for the CHILDREN OF THE WIND series. Kirsty lives in Melbourne with her husband and a gang of teenagers.

OTHER BOOKS BY KIRSTY MURRAY

FICTION

Zarconi's Magic Flying Fish

Market Blues

Walking Home with Marie-Claire

Bridie's Fire

NON-FICTION

Howard Florey, Miracle Maker

Tough Stuff

KIRSTY MURRAY

Children of the wind

Becoming Billy Dare

First published in 2004

Copyright © Kirsty Murray 2004

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web:www.Allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Murray, Kirsty.

Becoming Billy Dare.

For children.

ISBN 978 1 86508 735 1.

I. Title. (Series: Murray, Kirsty. Children of the wind; bk. 2).

A823.3

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body

Designed by Ruth Grüner

Set in 10.7 pt Sabon by Ruth Grüner

Printed by McPherson's Printing Group, Maryborough, Victoria

3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Teachers' notes available from www.Allenandunwin.com

To Theodore William Harper, philosopher, actor and inspiration

Contents

Acknowledgements

1 Goodness

2 Into the dark

3 Small temptations

4 Sanctuary dove

5 Wise men and fools

6 Crazed moon at Christmas

7 The faithful departed

8 Falling from grace

9 Come back early or never come

10 The Lapwing

11 The gift of a knife

12 Jonah

13 Bones of a man

14 Daring Jack Ace

15 The wild child

16 Stealing Violet

17 Keeping faith,

18 Gunyah Station

19 Scribe

20 The Lilliputians

21 Mean streets

22 Beggarman, thief

23 Fire and gold

24 Ned Kelly by night

25 Where in the world

26 Taking chances

27 The unexpected

28 Perfection

29 Lightning Jack

30 Rustlings in the dark

31 Becoming Billy Dare

32 Limelight man

33 Welcome strangers

34 Wherever green is worn

35 The great rescue

36 Bright thresholds

Author's note

Acknowledgements

As with each of the books in this series, there are countless people who helped me bring Paddy's story to life.

In Ireland: Father Padraig O'Fiannachta, Con Moriarty, Gerry O'Leary, the Clarke/O'Neill family, Alice Perceval, Margaret Hoctor, Ruth Lawler, Angela Long, Paddy Hines, Patrick Sutton, Colm Quinn and Oliver P. Murphy.

In Australia: Judy Brett, Graham Smith, Joanna Leahy, Peter Freund, Jocelyn Ainslie, Ben Boyd, Don Blackwood, Reuben Legge, Matthew Taft, Penni Russon, Sarah Brenan, Rosalind Price, and with loving memories of Helena Holec.

The list of authors and historians whose understandings of the past I depended on is too long to detail but I would particularly like to acknowledge the work of Michael Cannon, Andrew Brown-May, Mark St Leon and Margaret Williams.

For enriching my research by making their archives and collections available I would like to acknowledge the State Library of Victoria, the Caroline Chisholm Library, the Performing Arts Museum, All Hallows College, Dublin, the National Library of Ireland and Belvedere College.

The poem that John Doherty and Mr Maloney teach Paddy is ‘The Stolen Child ’ by William Butler Yeats. The poem that Paddy translates from Latin is an eleventh-century Invocation by Bishop Patrick that was sourced from The Writings of Bishop Patrick 1074–1084, ed. Aubrey Gwynn, and translated from the Latin by Ben Boyd. The song that the shearers sing with Paddy and Violet is from Waratah and Wattle by Henry Lawson. On page 223, Paddy also briefly quotes Macbeth.

I would also like to acknowledge the support of the Australia Council.

And to the thieves who stole the first draft, thanks for teaching me that a good story is more than simply words on a page.

Every book is an adventure, a trial and a great joy. Thanks to my family for sharing the ups and downs of this one: Ken, Ruby, Billy, Elwyn, Isobel, Romanie and Theo.

1

Goodness

Paddy opened the carriage window and stuck his head out, feeling the cold wind whip his face.

‘You daring me still?’ he called over his shoulder. ‘You know I'll prove you wrong, Mick.’

Mick stepped away from the rush of cold air. ‘I dare you then. Go on,’ he said, his teeth chattering.

‘Pull the blinds down in the compartment,’ instructed Paddy,‘and if the conductor comes by, mind you don't let him shut the window.’ He undid the buttons of his soutane, and shoved the long black robes into Mick's hands. The ground rushed away beneath him as he slipped through the narrow opening, reached up to the edge of the carriage and hoisted himself onto the roof. The smell of coal was strong. He had to stretch his arms wide to keep himself from sliding sideways. For a moment he lay flat on his belly, his eyes stinging from the smoke and wind. He pressed his cheek against the cold metal and thought of that moment at Gort when he'd hugged his mother one last time, feeling the smallness of her, like a frail bird.

The whistle blew as the train veered around a bend and Paddy found he was sliding towards the edge. His shirt rode up and his bare skin scraped against the metal. He could hear Mick calling and he groped for a hand-hold, curling his fingers over a narrow ridge.

‘Sweet Jesus,’ he muttered, as he lowered his legs over the side,‘please don't let him have shut the window.’ Then his feet found the ledge and he scrambled back inside, laughing with relief.

Mick sat down on the dark leather seat, put his head in his hands and groaned.

‘Sure I thought you were dead, Paddy Delaney. And how was I to be telling my parents that the little priest had jumped out a window!’

‘I didn't jump, I'm no

t a priest yet and you owe me sixpence.’

Mick sighed. ‘My good pennies for America wasted on a mad Irishman.’

Paddy buttoned up his soutane and sat down beside Mick. ‘How can you be grudging me sixpence when you're about to have the time of your life and I'm bound to studying for years and years?’

‘And how will you be taking a vow of poverty and obedience, when you've always been the one for taking a dare and robbing an innocent soul of his pennies?’

‘That was the last bet you'll ever lose to me, Michael MacNamara. I'm turning over a new leaf. I promised my mam I'd be good. I'm giving up playing the devil.’

‘So you say,’ said Mick, handing over the sixpence. ‘But the devil is good to his own.’

‘God's truth!’ swore Paddy,‘Once I'm in Dublin, I'm going to be a new man.’

Mick folded his arms across his chest. ‘Well now, if that's the last bet I'll be losing to you, I'll wager I can beat you in a wrestle.’

Paddy laughed and jumped on Mick. ‘We're not in Dublin yet!’

The engine blew a blast of steam into the chill afternoon air. Paddy studied the faces of the people hurrying along the platform, wondering how to find his uncle, but when he saw a bald man with intensely blue eyes and a face as red as scoured brick striding towards him, he knew it had to be Uncle Kevin. Hurrying to catch up was a small, brown-haired woman.

‘Patrick Delaney, is it?’ Uncle Kevin clamped a thick hand on Paddy's shoulders and turned him sideways and then straight on, as if he was a prize specimen.

‘You're a big lad for your age,’ he said. He gestured to the woman. ‘This here is your Aunt Lil.’

‘It's grand to meet you, Aunt Lil. My mammy sends her kind regards.’

Aunt Lil stared at him, her expression startled. ‘Sure but we're glad you've come at last.’ Her hand trembled a little as she reached out and touched Paddy's cheek and then his hair. ‘No one warned us you'd be such a handsome one! Bless you, look at this hair, Kevin, it's like pure gold!’

Paddy smiled. ‘I used to have curls, but a boy can't be going to school with curls, so Mam cut them off on my last night home.’

‘It must have broke her heart to see those golden locks fall.’

‘Sure, she was crying as she swept them up,’ said Paddy, grinning.

Uncle Kevin snorted. ‘Don't be fussing now,’ he said gruffly. ‘You'll make the boy as vain as his father.’

Paddy fought down the sharp reply that leapt to mind. He'd promised his mother he would give up answering back to his elders, along with all his other bad habits.

Uncle Kevin turned and led the way, shouldering through the crowd like a bull amongst cattle. Outside the station, he hailed a cab, driven by a man in a battered top hat. Paddy's bad mood dissolved as he leant out of the window, excited by his first sight of Dublin with its clattering trams and streets thronged with people. When the cab crossed over the Liffey River, Paddy leant so far out that Uncle Kevin grabbed him by the scruff of the neck and hauled him back in.

‘You're not a wild goat from the Burren any more, young man. You're a seminary boy, or soon enough will be. They won't be standing any nonsense at St Columcille's.’

Paddy slumped in his seat and eyed Uncle Kevin with annoyance. It was obviously going to be harder to be good when Uncle Kevin was around. He was relieved when the cab pulled up outside a tall, narrow shop with a canvas awning and wooden trim painted dark green. Above the door, in gold lettering were the words K.M.Cassidy, Tobacconist.

Paddy jumped out of the cab and stood staring through the plate-glass window at the display - pipes with carved ebony bowls, pipes with bone handles, tobacco tins of all sizes, boxes of cigars, and even special knives for cutting tobacco. When the door of the shop swung open, a rich, heady scent drifted into the street. Paddy breathed deeply, savouring the aroma. It reminded him of his father. The only memory Paddy had, from when he was very small, was of a man lying down beside him on a big bed beneath a window and the scent of tobacco was all around them.

A maid took Uncle Kevin's hat and cane from him as they entered the flat above the shop, and then disappeared with Aunt Lil. In his study, Uncle Kevin settled down in one of the deep armchairs before the coal fire and gestured for Paddy to take the other. The odours of old leather and stale smoke were thick in the air. Uncle Kevin pulled out a pipe from his pocket and began packing it with tobacco.

‘This is a great day, Patrick, a great day.’

Paddy wasn't sure if he was meant to say anything. He wriggled uncomfortably in the deep armchair. Uncle Kevin leant forward and rested one hand on Paddy's knee.

‘What is the happiest moment in a man's life?’ he asked.

‘When he receives his first communion?’

‘Aye, that's the happiest moment.’

Paddy tried to think back to his first communion, but all he could recall was the cake that his mother had made for the celebration. Uncle Kevin took a silver-framed photo from the mantelpiece and handed it to Paddy.

Two pale-eyed boys, as alike as any human beings could be, stared out at Paddy. They were dressed in dark clothes, and their faces were as still as corpses, their figures shadowy against the faded background.

‘That's your Uncle Patrick and me on our happiest day. And there's only one day that would have been happier. If Patrick had lived to take his vows, sure that would have been a blessed occasion and we would already have a priest in the family. You know, your Uncle Patrick told me he could hear the voice of God calling him. If he had lived, he would have been the finest priest in all Ireland. A bishop, an archbishop even. Perhaps, Rome.’

He took the photo from Paddy and placed it reverently back on the mantelpiece.

‘And now we have you. Your mam has said you were for the church ever since you were born. And here you are, off to St Columcille's, the first step on the great journey. Sure, your Uncle Patrick never had such a grand opportunity. The Jesuits will make a great man of you, Patrick.’

Paddy pulled at the collar of his soutane and frowned. He hated being called Patrick. It made him feel as if he were living in the shadow of his lost uncle. He wished Aunt Lil would call them for tea.

Uncle Kevin crossed the room and pulled open a drawer in his desk.

‘There's something here I want you to have, Patrick. Something I've been saving.’

Paddy stood up and Uncle Kevin took his hand, turning his palm over and then folding it shut on a string of well-thumbed coloured-glass rosary beads.

‘They were your Uncle Patrick's,’ he said, his blue eyes growing watery.

‘Thank you,’ said Paddy, uncomfortably. There was something macabre about the touch of the cold rosary beads. It was as if he was putting on a dead man's shoes. He shuddered and slipped the rosary into his pocket.

2

Into the dark

Paddy was glad when Aunt Lil pushed the door open and came in with the tea things.

‘Sure, Aunt Lil, this is a feast!’ he said.

Aunt Lil laughed. Over tea, she asked him all about the long journey from the summer fields of the Burren and laughed again when he described the hapless Liam O'Flaherty and his broken-down cart struggling to get them to Gort in time for the train. She urged him to eat up, pressing more cream biscuits on him.

The shop bell rang and Uncle Kevin stood up.

‘You can stop your fussing, Lil. John's here to take the boy,’ he announced.

Down in the street, Uncle Kevin slung Paddy's bag into the old cart parked by the kerbside.

‘This here is John Doherty.’ Uncle Kevin nodded at the driver, a long-faced man with black hair cropped close under his cap. ‘I can't be leaving the shop, so John will be taking you out to St Columcille's. Every Sunday, after mass, he'll bring you to us for your dinner and then return you to college in the evening. You're to mind him, boy. Mind John on the journey, and mind the Fathers and the Brothers at the college. And remember us in your prayers.’

Aunt Lil tapped Paddy awkward

ly on the arm. ‘Sure, but we'll be looking forward to next Sunday, Patrick.’

Paddy could tell she wasn't used to hugging children. He thought of his mother and the way she always hugged him before they parted, even if he was only heading out to play.

‘Hurry along then,’ said Uncle Kevin. ‘Don't be keeping John waiting.’

The cart moved out into the city traffic. They crossed the Liffey again and Paddy twisted around to stare back at the statue of a man who stood watching over Sackville Street.

‘Who's that monument of, then?’ asked Paddy.

‘Who else but the great man himself, Dan O'Connell,’ replied the carter.

‘He was a great man, it's true,’ said Paddy. ‘I'm hoping to be a great man myself one day - a priest.’

‘A priest, you say?’ John Doherty turned to smile at Paddy, his brown eyes creasing. He pulled out his pipe, stuffed it full of tobacco, and lit up.

Paddy put his elbows on his knees and leant forward in his seat, staring at the road ahead. ‘One day, Pm going to be a missionary. I'm come from Clare to study for the priesthood. My mam says there's a million heathen in Africa that need saving so I'll be off in Africa, sailing the rivers and slashing through the jungles.’

‘Wisha, if one of my little nephews were to be a holy priest, I'd be right proud that he'd been called.’

‘Well, I haven't exactly been called yet. See, I was the first and the only one of my mam's boys not to die. All the others, seven of them, they all went to God, and Mam promised him that if I was to live, then the Holy Church would have me.’

‘Your mother's a good woman, to be parting with her only child.’

‘Oh, there's still my sister Honor at home. She's been away in Belfast since I was small but she's come back now to be with Mam. Mam says my dad and all those dead brothers that are with Jesus, they're watching over me and on account of them, she says I'll be saving souls in Africa.’

‘Africa, you say,’ said John Doherty, and he laughed, a short bark of a laugh that quickly turned into a hacking cough. He spat a wad of dark spit onto the road and wiped his mouth on the back of his sleeve.

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish Bridie's Fire

Bridie's Fire Vulture's Gate

Vulture's Gate The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie

The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie A Prayer for Blue Delaney

A Prayer for Blue Delaney The Year It All Ended

The Year It All Ended India Dark

India Dark Becoming Billy Dare

Becoming Billy Dare The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong

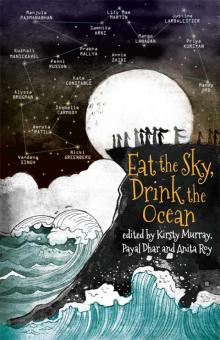

The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean