- Home

- Kirsty Murray

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean Page 2

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean Read online

Page 2

These trees had been purple in the spring, green throughout the summer, shading the street, the footpath, the rows of terrace houses.

Now they were dead, what had been footpath was dirt and gravel, indistinguishable from the street, and most of the houses were gone. At the coolest time of year, in the dark, the city sent out teams to shore up the buildings marked for preservation.

Poppy felt a curious scratching between her shoulder-blades as if someone were watching her. She turned. All she saw were scattered lights from the city’s hospitals.

A beetle scuttled over her suited foot. She lit up her right palm: black and red shell, yellow body. Plague beetle. They ate everything: plants, other insects, anything decomposing.

Some tried to eat the fossilised trees.

Long ago it had been bad luck to see a plague beetle. Now they were everywhere, a few even made it into the city. Poppy figured that meant they were all doomed: living mostly underground, in an inadequately shielded city, on strict rations and never enough water, far from India, from the Americas, from the places that were more than merely surviving.

Poppy quickened her pace, saw another beetle, crunched it underfoot. She smiled. Plague beetles were why so many greenhouses had been abandoned. She felt good killing them.

Her mother said every life was sacred; Poppy didn’t agree.

Her shoulderblades still prickled. She turned. Saw nothing. If her suit were newer her screen would show her behind, above too.

What if there was a secret dwelling of survivors? They’d prey on anyone foolish enough to leave the city alone, wouldn’t they?

She heard what sounded like a howl. Couldn’t be the wind; there was no wind. She turned slowly. The moon was bright enough to produce shadows, but the shadows were of dead trees, dilapidated buildings. Something flickered in the distance.

The sky broke open with a thousand jagged shards of light. Something boomed. Poppy raised her suited hands to her suited ears. It sounded like an explosion. But she saw no fire.

Thunder. Lightning. An electrical storm.

There’d been no warning. Even now as the thunder crashed, her suit gave no weather warnings.

A call pinged. Her mother. Poppy was half-tempted not to take it.

‘Hello,’ Poppy said at last.

‘The lightning is too close. Come home.’

‘I thought you weren’t talking to me.’ Poppy could hear the whine in her own voice and wished she could take her words back.

‘An electrical storm is dangerous.’

Poppy couldn’t argue with that. She walked closer to the buildings while quickening her pace so her mother could see on her screen that Poppy wasn’t turning around. She took a sip from her suit, just back from its check-up, cleaner, and recycling water and air better than it had in months. The water tasted almost sweet. That would change.

The thunder crashed again, so close, so loud, the ground beneath her feet shifted, she tripped, landed heavily in the loose dirt. Her feet sliding on gravel, the weight of her pack pulling her backwards.

Poppy heard something rip.

Felt heat, burning. Her suit, her back, at the lower ribs, just below her pack, exposed to air.

She leapt up, ignoring pain, walking faster, groping for her pack. She had to fix the tear. She had to keep moving. If she stopped, the beetles, and who knew what nasty bacteria, would get in through the tear, into where her skin was burning.

‘What is it, Poppy?’

Poppy wished she hadn’t taken the call. ‘Nothing. Tripped. Distracted by talking to you. I’ll call again when I get to Grandma’s.’

She clicked off before her mother could respond.

Poppy opened her pack, pulled out tape, patches, twisting to place a patch on her back, to tape it in place. The tape twisted, stuck to itself. There wasn’t much left. She pried it apart, slowly, patiently, while still walking, while her back burned, while she ignored her mother calling. She sipped more water trying to stay calm.

She kept moving, eyes on the tape in her suited hands, shifting her gaze occasionally, to glance at the ground.

Tape separated, she twisted to run it along the edge of the patch leaving no gaps, to make sure it was in place over where it burned. Her sweat ran salt into the burning. She didn’t scream. She hadn’t since she was three years old.

The patch in place, pressing hard along the tape, forcing it to adhere. Miracle tape. She’d made condensation traps out of it. Grandma said you could build a spaceship from it.

Another crash of thunder, shaking the ground. Poppy tripped but did not fall. Her shoulderblades still itched. Someone couldn’t be following her. She would’ve seen them. She was almost at the end of the island, if she turned back now … Poppy could hear her mother’s told-you-sos. Dry storms always passed quickly.

It felt like the patch was in place. It had to be. If she’d had a better suit …

Poppy didn’t know how many layers of skin she’d lost. Wouldn’t know till she returned, pointless thinking about it.

She passed the Yellow House. Seven stories tall. No one knew now what it had been. Or why it was called that. If it had ever been yellow it was a long time ago.

The ground started to slope. The water wasn’t far now.

Poppy heard howling.

Not her imagination.

It couldn’t be a wolf. Though that’s what it sounded like. She’d seen vids of them. Yellow eyes, strong jaws. There’d never been any here. Dingoes, long ago. Even longer ago, marsupial lions. Those were the only things that had howled here. No mammals, no reptiles, very few species could survive on this scorched earth, under this hot sun, with these poisons in the air and in the soil. Only humans found ways to eke out a kind of survival.

The howl had to be a recording.

Poppy walked faster.

I can help you with that.

Poppy spun around. There was no one.

The voice was inside her suit.

She felt chilled. She hadn’t heard a ping, hadn’t accepted a call. The caller had no ID. Someone had hacked her suit.

She shut off the call.

I can make sure your suit is patched securely.

She blocked the call.

I can get you to your grandmother’s house.

Nothing worked.

‘Who is this?’

Someone who can help you.

She was sure she’d heard that voice before.

The howling again. A human wolf.

I can get you to your grandma’s house.

Shut up, she didn’t say.

More thunder, more lightning.

Jagged lights across the water. The sea. Calm and low tide.

Two boats left. Both marked as seaworthy. People were careful to wipe those marks off when a boat started to take in water and they didn’t have time to repair it. The few who lived out here depended on the boats being well maintained.

Poppy set the oars in place, looked around one more time. Whoever the mysterious caller was they were not in sight. They were probably back in the city. Playing games.

She rowed towards her grandma’s island, ignoring the pain of her back, the feeling of being watched.

Hard and fast, she rowed, finding her rhythm. She would get to Grandma Lily.

Her mother called again.

Poppy ignored her.

I can fix your suit, the voice said. Get you to her quickly, safely. Then home. No charge. No debt.

She tried to shut the call off.

I’d like to help you. I like you.

The voice buzzed in her ears, making her wish she could wash. When she reached her grandma she’d scrape herself clean.

As she approached the shore she heard the howling again.

She sipped at her suit. Only the barest trickle. That wasn’t right. She sipped again. Mere drops.

She’d fa

llen once. Surely that couldn’t have damaged the recycling function? Her suit was old but solid. She’d fallen a million times, been banged into even more. The suit had just been repaired.

She was almost there now. In an emergency she could always call a courier. Or Emergency Services.

A real emergency. Not a bit of lightning and thunder, and some creepy prankster hacking her suit’s communications.

She splashed through the shallow waters, pulling the boat high onto the shore. Laying the oars inside. Her back burned but she didn’t think it was worse. Patch was holding.

A howl surrounded her as she moved up the beach. As if the animal – it couldn’t be an animal – was right there. She spun. Nothing.

More sweat. Fear sweat.

She took an involuntary sip. Almost nothing. But all that sweat? Should be a steady flow of water. Was the suit clogged?

I can help you anytime, darling.

She almost told him where to go.

Instead she called ES. ‘I’d like to report a hack. Someone’s talking to me without permission, without ID.’

The operator put Poppy on hold, which meant she was low priority. She wasn’t an engineer yet. Her mother wasn’t important. She’d voluntarily left the city. It was only a hack.

Poppy called her mother to tell her what was happening so her mum didn’t hear it from someone else. The speed of gossip was faster than the speed of light.

‘Just a prank,’ she told her. ‘No need to worry. Almost at grandma’s.’ She cut her off before she could I-told-you-so Poppy to death.

They won’t help, the voice told her. They can’t track me. You won’t get to your grandma before I do.

She was still on hold. Maybe the operator was already monitoring these calls.

That howl. Again.

Poppy barely kept her scream inside.

She ran. She didn’t care if whoever it was could see her speeding up. That they knew they’d rattled her. She would get to Grandma.

Her mother called. She ignored it.

You can’t hide. Your suit is red. It pops. Like blood on snow.

Poppy had never seen snow. No one she knew had.

A lightning strike too close by. More thunder. In the same direction as her grandma’s.

Sky’s on fire. Is that your grandma’s house?

Poppy ran faster, dirt kicking up. Old streetlights protruding from what had been the road, offering no light, plastic and wires long since stripped away. More dead trees. Power poles with no wires, connecting nothing to nothing.

Then, at the top of the hill, her grandma’s house. The only house not in ruins.

She almost shouted, Yes!

But lightning flashed. The front of the house momentarily visible as day. Then back to moonlight.

It was enough.

Poppy had seen her grandma. Grandma Lily wouldn’t be coming back to the city. She wouldn’t be saying goodbye.

The house’s seal was broken.

Grandma Lily was on the remains of the porch, leaning on the railing.

Without her suit.

Dried-out eyes open, skin turned leather, hair gone.

Grandma Lily had long white hair she wore in a bun. She never wore her suit inside, only out. No matter how hot it got. That’s how Poppy knew the colour and texture and smell of her grandma’s hair. The hair that was gone.

Every window was broken. The porch glittered with shards of glass.

The seal wasn’t just broken; it was shredded.

Should’ve told you it was too late, shouldn’t I?

Poppy ran into the house, grabbed everything that wasn’t destroyed. Books had disintegrated, most of the plastics melted, but some of Grandma’s hardware was locked away. Poppy put as much as she could into her pack. Grandma’s knife too. She’d designed it herself, could cut through any-thing. Totally illegal.

No tears for Grandma Lily, only burning eyes.

Poppy sipped again. No water at all.

She checked her grandma’s condensation traps, the ones she’d helped her build. Poppy attached her suit, extracted all the H2O she could.

The sky cracked open. Thunder, lightning, at the same time. Her ears echoed with it. The afterimage played across her eyes.

Time to leave.

She paused on the steps, looking at Grandma Lily, wishing she could touch her. Skin to skin. One last time.

A howl filled the air.

Water fell from the sky. Giant drops bounced back from the unshielded steps.

Rain.

It fell loud and fast.

Rain.

It’s rain, the voice told her helpfully, you’re too young to have seen it before.

Poppy called ES and told them about Grandma Lily.

‘Your situation is being monitored,’ a different operator said. ‘Are you requesting extraction?’

It would cost too much.

In her suit she heard laughter. Only children laughed; by the time you were ten you’d learned to turn laughter off, or transform it into a smile.

‘Are you requesting extraction?’

‘No.’

Her mother called.

‘On my way,’ Poppy told her. ‘Grandma’s dead.’

Poppy felt her throat tighten. She clicked off before her mother could say anything.

Let me take you home, Poppy. In your little red suit.

‘No,’ she said. ‘You’re not even here.’

She was afraid. Her mouth was dry. She didn’t sip, wanting to make the water last.

The rain unceasing. If she could take off her visor, drink it in.

I am here.

Poppy spun around. Something was moving in the house.

She slid her hand into her pack, found the razor-sharp knife, unsheathed it, keeping her eyes on whatever was in Grandma Lily’s. She tried to get through to ES. ‘I’m being attacked,’ she told their message bank.

Someone grabbed her from behind. She slashed with her knife. Twisting to get away.

She felt something tear. Her knife through a suit, tearing through as she leaned away, almost losing her grip.

The person let go, tumbled down the steps. Howled.

Not a wolf. A man in a suit.

She held her grandmother’s knife out to the rain, watched the blood wash away, headed back to the city.

Cooking Time

Anita Roy

The minute the doorbell rang, I knew that something was wrong. The sound set my nerves jangling, as if it was plugged into my brain. My thoughts flew to the box in the basement, but before I could move, Marra had leapt up. ‘That will be Mandy,’ she said. ‘About time too.’ She opened the door. Two men stood in the street. They had AgroGlobal written all over them: dark suits, short hair, clean shoes, mirror-shades.

‘We’re looking for Miss Stella Jordan?’ the first one said.

Marra looked back at me, worry in her dark eyes.

‘You need to come with us,’ he said.

I got up. ‘Can I just … ‘

‘Now.’

There was no use protesting. I grabbed my bag and headed out.

There was a silver van standing outside. It looked so out of place in our street: like platinum dentures in a vagrant’s ruined mouth. ‘Nice wheels,’ I said. Suit One gave a small, tight smile as he held open the door.

‘Where are you taking me?’ I asked as we pulled out. We drove past crumbling buildings and old iron staircases, bumping over potholes.

‘Nothing to worry about,’ he said.

That wasn’t an answer, but it didn’t matter: I knew anyway. There was nowhere in Sector 87 to go, except for AgroGlobal.

At that moment, all I felt was angry. I’d always known that Mandy’s obsession would get us into trouble. But would she listen? Never. She would just get that look on her face, biting her lip, her eyebrows dra

wn together in a line.

‘I’m going to win, Stella,’ she would say to me. ‘I know I can cook.’

The weird thing is, she could, you know? She really knew how to cook. Nobody from the Sectors had even seen real food in their lifetime. It was fifty years since the Dying Out, thirty since the last of the great food wars, and twenty since AgroGlobal crushed the last aquaculture smallholdings, and established itself as the world’s largest – only – manufacturer of artificial food. ‘Newtrition’ they called it, which quickly got shortened to ‘Newtri’. ‘Newtri: Fuelling the Future,’ the ads say, ‘With over 70 great flavours to choose from, just squeeze and go!’ No mess, no fuss, and, although I’d like to say no hunger, at least people no longer starved to death. We owed everything to AgroGlobal – and they owned everything. Governments, armies, energy production, manufacturing, media, health care, communications, travel – temporal and spatial – you name it, they owned it. Everything needed people, and people needed fuel, and we all needed Newtri. That’s not to say that everyone was happy about it – I mean, look around you, right? But what choice did we have?

We all grew up on Newtri. Marra said us younglings were always clamouring for our tubes, but Mandy? She’d have just faded away if Marra hadn’t practically injected it into her. She was always the littlest of us, still is. We used to call her ‘2D’ – turn her sideways and she’d vanish. I always had to remind her to fuel up. ‘Yum, roast chicken and beans, and apple crumble. Your favourite,’ I’d say. She’d suck up a bit of her Newtri and then hand the rest to me while Marra wasn’t looking. I wasn’t complaining.

The driver took a right turn out of the Sector and onto the highway. I looked out at the dusty, ravaged land that stretched away on either side till it merged with the horizon, and thought back to that day two years ago when AgroGlobal TV had announced that the online Temproal Relocation Portal had gone live, and that the biggest show on the planet was about to be broadcast: MasterChef of All Time.

That was the day everything stopped. Schools closed, offices shut down, factories were silent – the skyways were empty, there wasn’t a single auto on the streets. Everyone was home watching.

It was the reality show to end all reality shows. Twelve specially selected contestants were sent back in time to battle it out every week for the ultimate prize: the MasterChef Golden Apron. In the words of Judge Cheng, ‘We’re not just talking real food, we’re talking about real cooking – you gotta work for it. You want to make fish? You got to catch the bugger first. You want to roast potatoes? You got to dig ‘em up. You gotta chop your logs and stoke up that fire before you even think about baking. You get me?’

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish Bridie's Fire

Bridie's Fire Vulture's Gate

Vulture's Gate The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie

The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie A Prayer for Blue Delaney

A Prayer for Blue Delaney The Year It All Ended

The Year It All Ended India Dark

India Dark Becoming Billy Dare

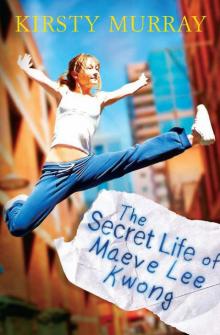

Becoming Billy Dare The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong

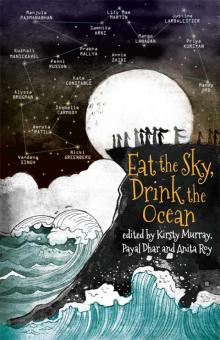

The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean