- Home

- Kirsty Murray

Vulture's Gate Page 3

Vulture's Gate Read online

Page 3

When she had finished, she looked back towards the hunting ground and sighed. She had taken every precaution before setting out in the dawn light. She had checked the sensors for any signs of human activity, and set the Wombator to work, programming it to dig another layer of tunnels beneath the upper burrow with emergency escape routes fanning out in two new directions. She knew she should turn back and hunt within the boundary of mines but the thought of bagging only another stringy feral cat again made her heart sink. There were no trees left inside her hunting ground, no desert fruits or roots to forage. Even though she knew Poppy would have disapproved, she herded the roboraptors through the minefield and into the wider desert. The morning was still and cool. It was the best time for hunting. The roboraptors were excited by the rising sun and gambolled along at her ankles making low purring sounds. The desert was her own.

She whistled two short commands and the roboraptors scurried ahead, fanning out into the low scrub, sending up little spurts of red earth from beneath their clawed feet. She hitched her string bag higher on her shoulder and picked up speed. She would have to walk for kilometres before she reached the old creekbed. It had been dry for decades but Bo knew that along its banks were the best places for digging out soft roots. An artesian well buried deep in the soil fed the long, stringy vegetables that she loved. She clipped some handfuls of greybeard grass and lined the string bag with it. It would be useful later for straining the sludgy black water that pooled in crevices along the creekbed. As she descended the rise above the creek, she pulled up a naked woollybutt tussock and added it to the string bag. It was small and dried-out but there was still enough seed on the long stems to make it worth taking home.

Reaching the dry creekbed at last, she squatted down on its banks and began to dig at the base of a withered tree. It took her twenty minutes to reach the root network that housed dead grubs and she was cross and sweaty by the time she found a finger-thick root and hacked it out. Her pleasure turned to disappointment when she peeled off the outer layer and found the grubs inside had turned powdery. She licked her fingers and dipped them into the chalky remains. At least the grub-dust was still sweet and nutty to taste.

She sat back on her heels and listened for the sound of the roboraptors. Last time they had ventured outside the hunting grounds, Mr Pinkwhistle had come back with a human hand in his jaws. Bo had scraped a hole in the nearest sandy patch of desert and buried it deep so the raptors wouldn’t find it again. No matter how hungry she was, there were some taboos she would never break.

Bo noticed a flurry of dust on the rise above the opposite bank and the tips of the roboraptors’ tails, erect and quivering. It seemed an odd place to catch something. Only a very stupid or sick animal would be caught on high ground where it was in clear view of approaching predators. Usually the roboraptors cornered their prey in outcrops of rock or chased them to ground on the flat plains.

Bo heard an unearthly cry. Seconds later, a boy stumbled over the crest of the rise and rolled down the sandy bank of the creek. Bo cried out in surprise. The roboraptors let out a group ululation of triumph and sped down the embankment to where the boy now lay motionless in the dry creekbed. Bo jumped to her feet and ran. By the time she got there Mr Pinkwhistle was standing on the boy’s head while the rest of the raptor pack perched on other parts of him, sending out the whine that signalled for Bo to help them carry home heavy prey.

Bo swatted the roboraptors away and knelt down. The boy was scrawny and his black hair stood up in ratty spikes. Bruises mottled his bare arms and the backs of his legs where his trousers were torn. He was out cold. Bo rolled him over and he flopped onto his back. The roboraptors danced on the spot with excitement.

‘Dumb,’ she said irritably, tapping each one between the eyes so they knew they had made a mistake. ‘Bad food.’

She leant in close to the boy’s body and sniffed his skin. He smelt of sweat and dust, something sweet and something sour. Resting her head against his chest, she listened to the sound of his heartbeat, felt the gentle rise and fall of his breath. She was relieved he was still alive.

The sky began to turn a smoky orange. Soon the morning cool would give way to scorching heat. If she left the boy unconscious in the dry creekbed, he’d be dead by midday. Maybe that would be a good thing. Then again, if he was an Outstationer’s boy they might come looking for him, and if they found him before he died he would tell them about the herd of roboraptors. They would suspect that a techno-hunter was nearby, that Poppy hadn’t been solo. She’d never be able to venture out of the hunting grounds again.

Taking her sharpest blade, she cut a section of bark big enough for a sled from a nearby tree. Using a coil of wire that was attached to her belt, she fashioned a series of harnesses for the roboraptors. She hauled the boy onto her shoulder, then laid him on the bark and snapped her fingers at Mr Pinkwhistle. As the roboraptors dragged the makeshift bark sled and its cargo up the embankment and back to Tjukurpa Piti, Bo swept their tracks with a bundle of twigs, scattering rocks in their wake to hide the trail.

When they had navigated their way across the minefield, Bo carried the boy, like a sack of bones, into the burrow. She took him down to a dark cave beyond the kitchen and laid him on a pile of rugs. He made a murmuring noise and curled into a ball, like a dead bilby.

For a while, Bo squatted beside him, studying his sleeping face. It had been so long since she’d seen a living human being up close that every aspect of his features fascinated her. His eyes were set wide apart and framed by high, arching brows. His long black eyelashes lay like butterfly wings against his cheeks. She traced her finger along his cheekbone. His skin was smooth and silky. His lips were dark pink and he had a small dimple in his chin. He was like a boy out of a fairy story. Before leaving him, she gently rested her cheek against his, savouring his sleepy warmth.

It was almost night when Bo heard the boy screaming. She slid down the connecting passage from the main living area. The sounds of his cries bounced off the stone and opal and echoed through the tunnel.

‘Shush!’ she said, as she held up a lumina and light filled the cave. Still the boy screamed, eyes scrunched up, mouth open wide.

Bo stared at him, perplexed. She’d forgotten how people talked to each other. It was easy with the raptors. One word was enough. She frowned and tried again. ‘Shush!’

The boy opened his eyes long enough to actually see her and he caught his breath. For a split second, he fell silent. Bo reached out a hand to him in a gesture of friendship and he started up again. His screams made her head hurt. She tried to remember what Poppy had done when she was very small and upset.

Gently but firmly, she grabbed the boy by both shoulders and leant in close to him. He was so surprised he didn’t struggle. Drawing a deep breath, she blew a soft stream of air onto the side of his neck. He tried to pull away but she drew him closer, wrapping her arms around him so he was pinned against her body. She cradled his head in one hand and blew a puff of air onto each of his scrunched-up eyelids. Startled, he stopped screaming and began to sob instead, his body growing limp in her arms. Bo continued to blow little puffs of air onto different parts of his face. His expression grew very still, as if he was frozen. He opened his dark eyes and looked at her just as she was blowing a long, steady stream of breath onto his forehead. ‘I’m not dead,

am I?’ he asked.

‘Dead?’ she echoed.

‘Maybe you’re some spook from the underworld? But I didn’t think hell would be like this.’

Bo suddenly felt aware of his body pressed against her own and the vibrations of his voice in her chest. She let go of him and backed away.

The boy shuddered and looked about him for the first time.

‘What is this place? Where am I? How did I get here? Who are you? Why did you do that to me?’

Bo knew she was meant to form whole sentences in answer to his questions but it had been too long. There were too many ‘who’, ‘what’, ‘where’, ‘how’ a

nd ‘why’s. She had to concentrate to retrieve the words from the back of her brain.

‘Tjukurpa Piti.’

‘You don’t speak English,’ he said, disappointed.

‘I speak. I understand,’ she replied. She could feel sounds bubbling up from somewhere deep inside her, her own words, not storybook ones. She could feel her mouth struggling to

form her thoughts into sounds, feel the warmth of them against her throat. It wasn’t like storytelling. She had to make words from nowhere.

‘Me Callum,’ said the boy, pointing to himself. ‘You . . . ?’

Bo rolled her eyes. The pretty boy was smiling at her as if she was a simpleton.

‘I am Boadicea,’ she said, trying to make the words sound sharp and resonant. ‘I found you.’

‘Are you one of those ferals, then?’ he asked, leaning in closer and studying her as if she was a curiosity. ‘You don’t look like an Outstationer, so what are you? Cybrid? Hybrid? Where did you come from?’

The questions ricocheted around the small chamber like bullets. Bo’s head began to ache. She picked up the lumina and started down the tunnel, crawling quickly back to the main room.

‘Hey!’ called Callum, as he dropped down onto his belly and started to wriggle along behind her. ‘Hey, Boo-ditchy, wait up. Don’t leave me. Don’t leave me in the dark.’

But Bo simply moved faster, wishing fervently that she had never brought the boy home.

7

TJUKURPA PITI

Bo could hear Callum gasping behind her as he scrabbled to catch up. When she reached the brightly lit living area, she felt a fleeting desire to seal the boy in the lower tunnels forever, but instead she waited for him, drumming her fingers on the kitchen table. He whimpered as he crawled out of the tunnel and stood upright. Bo followed his gaze as he stared at his surroundings in surprise. The cave was different now that it sheltered a stranger. The bulbous stone oven looked ungainly and the small kitchen and dining area seemed cluttered with wooden bowls and storage jars. Piles of salvaged old-tech machinery reached to the ceiling, almost obscuring the rough, stippled walls.

‘Crazy,’ said the boy. He took a step towards the weathered old couch but his body began to crumple before he reached it. He steadied himself against a wall and turned back to stare at Bo. ‘This place is bizarre. You live here?’

Bo shrugged and turned away from him, as though he would magically disappear if she ignored him. She gathered up

her long, silky brown hair and knotted it into a chignon before setting about tidying the kitchen. There was no reason to clean it but Callum’s presence made her see everything in a different light. She knew he was watching her and she pulled the ties of her shirt tighter, as if by fastening her clothes she could shut him out.

‘What’s this stuff?’ he asked, scratching at a jagged piece of sparkling silver-grey stone embedded in the wall.

‘Opal.’

‘Isn’t that bad luck or something?’

Bo ignored him and began straightening the shelves.

‘So it was you who saved me from those beastie things?’ he said after a long silence.

Bo could hear the shift in his tone. It was warmer, as if he might even admire her for helping him. Suddenly, the full meaning of what he’d said sank in. ‘Beastie things?’ she said.

‘Those giant rats.’ He frowned and put one hand to his forehead. ‘It was you that saved me when they came to eat me, wasn’t it?’

Bo laughed and then gave a low whistle. It was answered by a cry from deep underground, and the sound of the approaching roboraptors scurrying from the lower depths, spiralling up towards them. Callum’s face grew white. He lunged at the kitchen table, sweeping containers onto the floor as he scrambled to climb on top of it.

As the roboraptors swarmed into the cave, he picked up a wooden bowl to fling at them. Bo snatched it from his grasp.

‘No! These are children. Roboraptors. My children.’

Callum’s face crumpled in disgust. ‘You can’t mean children. They’re not even pets. They’re machines.’

Bo scooped Mr Pinkwhistle into her arms, holding him close with one hand and stroking the underside of his jaw. ‘My finest hunter.’ She frowned. She wanted her speech to flow but it was jammed somewhere in the back of her head, a whirling mass of complex sentences and lost words. She took a deep breath and they began to tumble out of her in a rush. ‘Poppy and I – salved, salvaged, built, repaired, made new. We soldered, wired all from wreckage, debris, rubbish, broken, twisted remnants.’ She sighed and thought carefully before she crafted her next sentence. ‘We made them whole again.’

‘What are you?’ said Callum. ‘Are you a chimera? Is there someone who owns you? What are you doing out here all by yourself?’

Bo blushed and carefully put Mr Pinkwhistle down on the floor. ‘What are you?’ she said sharply.

‘You can’t answer questions with questions.’

Bo shut her green eyes and stood still for a long moment, dredging from distant memory.

‘Once upon a time, I was very small. Poppy brought me here. I grew here. I belong here,’ said Bo, slowly enunciating each word with care. ‘You . . . fell from the sky.’

Callum laughed bitterly. ‘I wish.’

All the nervous energy drained out of him and he slumped onto his knees, as if every bone in his body was aching. He lay down on the table, flat on his back, and stared at the ceiling. ‘I ran away on the Daisy-May.’ He laughed at the accidental rhyme even as he winced, folding his arms tightly across his body. With his eyes shut he looked small and vulnerable again. He lay without speaking, his face etched with pain. Bo quietly herded the roboraptors into their den.

‘Come,’ she said touching Callum gently on the shoulder. He flinched momentarily but then meekly let her lead him across the cave to the long sofa. When she wrapped a fur rug around his shoulders, he didn’t resist. ‘The Daisy-May,’ he muttered. ‘I should go and find her. I have to find her before they do. I have to keep moving.’

‘Not now,’ said Bo, pulling the rug up to cover him, tucking him in as if he was a tiny child.

Callum looked drowsily up at the high shelves that lined the walls of the burrow.

‘What are they?’ he asked, pointing.

‘Books.’

Bo pulled a red volume from the shelf and handed it to him.

‘How do you turn them on?’ he asked

Bo laughed. ‘They are for reading, not for turning on.’

Bo took the book back and began to read aloud. ‘Once upon a time a king and a queen lived peacefully with their twelve children, who were all boys. One day the king said to his wife, “If the thirteenth child you are about to bear turns out to be a girl, then the twelve boys will have to be put to death . . .’ At first, she read haltingly but then the words began to flow, weaving a cat’s cradle of sounds that lulled the boy into a deep and dreamless sleep.

The sun hung low, a hazy orb in the western skies. Bo watched the boy squinting uneasily into the light. He had slept through the morning and woken early in the afternoon, insistent that he had to find his vehicle before someone else did.

‘Mines. Step carefully,’ said Bo, snatching Callum’s wrist and forcing him to follow in her footsteps. When they had reached clear ground, Bo tapped Mr Pinkwhistle three times on the base of his spine. He lowered his head and emitted a whirring noise in the back of his throat before scurrying out into the desert, sending little puffs of dust into the air.

Bo set out after the raptor at a run. Soon she heard Callum calling after her.

‘Boo, Boy, Bo, whatever you call yourself, slow down! We must be close by now,’ he said, as he struggled to keep pace.

Bo touched the tracks of the raptor. ‘No. Still far away.’

‘How did you get me back to your place if it’s so far?’

She turned to Callum and smiled. ‘My children helped.’

The boy grimaced and Bo wanted to shake him. Should she not call them he

r children? Was there something wrong with that? She had spent half the morning in the roboraptors’ den, practising her sentences on them so that she could speak properly to this boy and still she couldn’t seem to make their conversations work, couldn’t make him understand what she meant. She strode on, glad to leave him behind. Half an hour later, they crested a small rise to find a wide gibber plain of purple and orange stone stretching before them. Mr Pinkwhistle was hundreds of metres ahead, moving westward.

‘I know you think Mr Pinkwhistle is a top hunter, but I can’t see how he’s going to sniff out a motorbike,’ said Callum, leaning over to rest his hands on his knees, trying to catch his breath.

‘He will follow traces of your stink.’

‘I don’t stink,’ said Callum.

Bo stepped close to him and leant down to take in the scent of his skin. ‘You stink pretty,’ she said.

Callum drew away and clutched his shirt tightly against his sweaty chest. He looked out over the gibber plain to where Mr Pinkwhistle was running in widening circles trying to pick up a trail. ‘I wish I could remember more. There were some spiky plants where I fell. I was lucky I didn’t get pinned under the Daisy-May. The engine cut out. And then I walked for ages, heading over to that scrubby place where you found me. I don’t know why I can’t remember. I used to have a good instinct for lost things.’

‘Stink?’

‘No, instinct – not “stink”. Instinct – it’s, you know, when you feel something instead of knowing it.’

‘Like ’twitian?’ asked Bo. ‘Woman’s ’twitian?’

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish Bridie's Fire

Bridie's Fire Vulture's Gate

Vulture's Gate The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie

The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie A Prayer for Blue Delaney

A Prayer for Blue Delaney The Year It All Ended

The Year It All Ended India Dark

India Dark Becoming Billy Dare

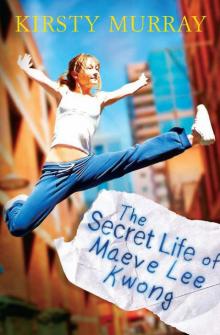

Becoming Billy Dare The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong

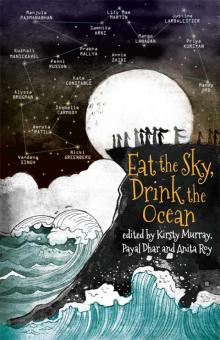

The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean