- Home

- Kirsty Murray

India Dark Page 2

India Dark Read online

Page 2

‘You’ve grown pretty too. Do you still sing? The way we used to on Sundays at my house?’

‘Some,’ I said.

‘You should come and try out for the Lilliputians.’

‘You mean the music-hall people?’

‘Of course! Did you think I meant midgets? That’s who I’ve been touring with – Percival’s Lilliputian Opera Company – singing and dancing our way across America. They’re putting together a new troupe now we’re home. Some girls are leaving and some have got too old. But you’re still a little darling. Mrs Essie will think you’re delicious. You could stay a Lilliputian for years. You must audition.’

‘I couldn’t!’

She wrapped her arms around my waist and kissed me on the forehead.

‘You don’t want to go to that dull old Continuation School,’ she said. ‘You’ll have to be a fusty, dusty teacher then, and never get married. Men don’t make passes at girls who wear glasses. Come away with me and all the boys will make eyes at us and think we’re darling sweethearts.’

‘I don’t care what boys think,’ I said.

I could feel the hot flush of blood rising up from my chest and burning my cheeks.

Tilly tapped my chin with one finger and laughed. ‘Or you could go to Bryant & May and burn your fingers off like Elsie Taylor did. Imagine. Who’d want a wife with a finger missing!’

‘I don’t care if no one wants me,’ I said, pushing myself away from her. But I looked at my hands and thought about Elsie Taylor’s missing fingers, about the stink of sulphur and the high red-brick walls of the match factory. I saw the fire and the darkness that lay ahead.

5

THE LILLIPUTIANS

Poesy Swift

The morning of the auditions, I went to Tilly’s house early but she had already left. Her ma explained that she had caught the tram with the Kelly sisters in Collingwood. Maybe she felt bad that Tilly hadn’t waited for me. l climbed on the tram at Smith Street, but I didn’t sit with Tilly and her friends. After a while she walked to the back of the tram and took my hand.

‘Why are you hiding up here all by yourself?’

‘You’re with your friends,’ I whispered, looking down into my lap.

‘Well, if you’re going to audition, you should meet the Kellys. C’mon.’

She led me to where the others were sitting, their skirts spread across the green leather seats.

‘Ruby, Beryl, Pearl, this is Poesy. She’s auditioning.’

I could see Tilly wasn’t sure of me. Not like when we were in the laneway. She wasn’t sure that she wanted to own me.

Beryl and Pearl barely nodded in my direction, but Ruby looked me up and down and then clapped her hands.

‘What a darling little creature,’ she said, ‘You are clever, Tilly. If she can sing, Mrs Essie will be rather pleased, even if the child is raggedy.’

I glanced at Tilly and saw her purse her lips, as if she’d sucked a lemon. I smiled uncertainly and tried not to mind when Tilly sat down and pulled me roughly onto her lap, as if I were her new doll.

Ruby was the eldest Kelly sister but she still wore her honey-blonde hair long and loose. It curled around her shoulders and her heart-shaped face. She was so pink and white and dimpled that she reminded me of the girl in the posters for Kodak. But then all the Kelly girls were picture-book pretty in their crisp white clothes, new black stockings and shiny, black-buttoned boots. I smoothed the fabric of my brown dress and wished I was invisible. Ruby leaned forward and her breath was sweet and minty but her words were meant only for Tilly.

‘You remember that gentleman who followed us from city to city to see all our performances?’ she asked. ‘Well, he’s been writing to Tempe and he wants her to go back to America and marry him.’

‘But he was peculiar,’ said Tilly.

‘Of course he was awfully odd. She won’t go. But it’s rather nice he asked. Do you remember he kept sending chocolates backstage and Tempe wouldn’t touch them?’

‘Oh, yes, and the boys stuck their fingers in all the soft-centred ones.’ Tilly laughed.

Chocolates and flowers and gentlemen admirers. America – it made me shiver to think of it. I’d been to Ballarat once, before Dad died. Only once. Yada and Mumma seemed to think Richmond was the whole world.

The tram rattled through Northcote and stopped at a flat, dusty intersection in Thornbury. I followed Tilly and the Kelly girls along Darebin Road. My stomach began to ache.

Balaclava Hall was a white weatherboard building with long windows and a small porch at the front that was crowded with children and their parents.

‘Tilly?’ I whispered, in awe of everyone’s stiff curls and layers of lace.

‘Don’t worry,’ she said breezily. ‘You’ll be better than the lot of them.’ She grabbed my hand and dragged me up the front steps of the hall.

‘This is Poesy Swift, Mrs Essie. The girl I told you about.’

I tried to keep my gaze steady and look Mrs Essie squarely in the face. She had grey hair pulled back in a tight bun and she studied me in a way that made me burn, as if she saw straight through me, as if she saw straight into my heart, and knew I was hopeless. Beside her stood her brother, Mr Percival. Mr Arthur Percival.

He looked kind, that first day, and so smoothly handsome with his sparkly blue eyes that I felt too shy to meet his gaze. He wore a silvery-grey jacket, lovely slim-legged trousers and a dove-grey tie. You’d never have thought he and Mrs Essie were brother and sister. To look at, Mr Arthur could have been her son, even though he was thirty-five years old, old enough to be my father. He tipped his soft derby hat onto the back of his head and smiled at me, and his eyes grew crinkly with cheerfulness. He took off his grey reindeer gloves and he spoke my name, as if we were old friends.

‘Poesy, you mustn’t be shy with us,’ he said, touching my chin lightly. ‘The children in our company have a marvellous time with singing, dancing, costumes, everything a girl enjoys. And if you pass muster when you audition, we’ll train you to be a proper little actress. Is your mother here?’

‘My mother had to work today and my grandmother is taking care of my little brother. But they’re very happy for me to be here,’ I lied.

‘And have you prepared a song for us?’ he asked.

I felt the blood drain right down to my boots. I hadn’t thought about a song. What had I been thinking? I’d been thinking about being given boxes of chocolates and America and sailing away from Melbourne and never having to change Chooky’s wet sheets ever again.

‘Oh, Poesy knows thousands of songs,’ interrupted Tilly. ‘At our musical Sundays, at my place, she was always larking about and showing off and singing louder than everyone else, weren’t you, Poesy?’

I grinned and nodded like an imbecile. Had I been a showoff? I always thought it was Tilly who stole the limelight. In school they had called her ‘Little Miss Noticebox’. I never felt anyone took notice of me.

On Mr Percival’s instruction, I stepped up onto the low stage at the far end of the hall. My head exploded with songs but they were all hymns from Sunday School. ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’ didn’t seem the sort of song the Lilliputians would sing. I looked at Tilly and made my eyes wide. She was mouthing something at me and miming the gestures of a song behind Mrs Essie’s back but I couldn’t think what it was. What on earth had made me imagine I could be like Tilly, with her dark, glossy curls and her wide, laughing mouth? All of a sudden, I wanted to go home.

So I sang the only song I could think of: ‘Home, Sweet Home’. I knew that Tilly always acted out her songs so I put my hands together as if I was begging to be taken to my home, sweet home, and disdaining the pleasures of palaces for my humble home. No place like home. And that was true, there was nowhere like my cottage. Nowhere as empty and as full of misery.

I let the song fill me up, the notes swelling in my chest. I loved the way singing made your head feel lighter, as if the breath and the sound were one and the same. As if you becam

e the sounds and the song. I knew I didn’t look so mousy when I sang, I knew my cheeks turned pink and my eyes shone, and I hoped, I prayed, that maybe I looked a little more like Tilly. Mr Arthur watched me closely, noting every gesture I made, taking in every aspect of my figure, but Mrs Essie tipped her head to one side and listened with her eyes shut as if all she wanted to gauge was the sweetness of my voice.

Afterwards, I played chasey around the back of the hall with two of the littler girls who were waiting outside. When we were tired, we sat underneath an old ghost gum.

‘Have you had your audition already?’ I asked.

‘Thilly!’ said the smallest one, her lisp so thick I wasn’t sure if she was exclaiming Tilly or silly. ‘We’re already with the Lilliputhianth. We don’t have to audition.’

‘What’s it like travelling with the troupe?’ I asked.

‘It’s jolly hard work,’ said both the girls at once.

‘Oh poo,’ said Tilly, sitting down beside me. ‘Don’t listen to Daisy and Flora. It’s much harder having to sit in a stinky old classroom. What would you know, either of you? You’ve never done anything else.’

Tilly turned to me and held my face in her hands. She studied me closely, as if there was something about me that she needed to discover, something that puzzled her.

‘This is your chance, Poesy. I heard Mrs Essie and Mr Arthur talking about you. They like you.’ I could hear a faint note of incredulity in her voice, as if, despite her promptings, she’d thought I would fail. ‘Now all you have to do is make sure your mother agrees. They won’t take you if your mother doesn’t sign the papers. If she does, we’ll be able to sing and dance our way across America.’

I hoped she couldn’t feel me trembling. Trembling with longing.

‘It could be the making of you, Poesy,’ she announced. ‘If you join up, we could be friends again.’

‘Aren’t we friends anyway, even if I can’t come?’

‘Don’t turn my words around. Of course we are, but if you can make your mother sign the papers, we’ll travel the world together. All you have to do is tell her. Tell her tonight.’

6

A DREAM UNSPOKEN

Poesy Swift

I didn’t tell Mumma. I didn’t breathe a word. That night I sat quietly at teatime and squashed my egg into little pieces while Yada and Mumma argued back and forth across the table. Fat tears rolled down Chooky’s face and plopped onto his plate but I couldn’t feel anything. It was the same argument they had been having since the start of the year.

‘Poesy doesn’t need to finish the term,’ said Mumma. ‘It won’t make any difference to whether she finds a job. Dimmeys are hiring. This is her chance.’

‘Dimmeys are looking for girls of fourteen!’ Yada slapped the table with her skinny hand. ‘Why, she looks no more than ten!’

‘But she’s not ten. She’s thirteen and old enough to earn her keep. Dimmeys put the smaller girls in the back of the shop. If she starts now, she could work her way up.’

‘She’s still a child, Adeline!’

‘Ma, you make it sound as if I’m forcing her into slavery,’ said Mumma with the bitterness that always tinged her voice when they fought over me. ‘I’m not suggesting Bryant & May.’

I thought of Elsie and the other girls who lied about their age and found work dipping matches or stirring jam at the factory across the bridge. But no one would want me. No one except the Lilliputians. Yada was right. I did look like a ten-year-old, even though it was three months since I’d turned thirteen.

‘I want her to get an education,’ said Yada. ‘Poesy is more than clever enough for the Continuation School.’

I should have said something then. I no more wanted to go to the Continuation School than I did the match factory. I wanted to sing. I wanted to be with Tilly. I wanted her world. But Yada would have been horrified to have a granddaughter on the stage. And Mumma would have misgivings. She’d never liked Tilly. I cleared my plate and left the kitchen.

While they argued, I stood in front of the mirror in Yada’s bedroom and bunched up the back of my nightgown so the front stretched smooth and flat against my chest. My narrow shoulders looked like the spiky nubs of wings and my face was as pale as a new moon. How could I ever be a star of the stage?

Chooky came into the room and stared at me, his face sticky with dirt and tears.

‘Do you think I’m pretty enough?’ I asked him. He put his thumb in his mouth and nodded. I turned back to the mirror but there was nothing pretty in the face of the girl who stared back at me. Her face was heavy with sadness.

Downstairs, the fight grew louder, the angry voices sharper, aiming to wound. A door slammed, and another, and then Mumma screamed. It set Chooky sobbing again and sent me running to the top of the stairs. Mumma was kneeling at the bottom, holding her wrist with the other hand. She looked up at Chooky and me. ‘She didn’t mean it. It was my fault. I put my hand in the door. She didn’t mean to slam it so hard.’ But Chooky and I knew. It wasn’t the first time Yada had hurt Mumma.

Yada opened the kitchen door and stared.

‘Darling,’ was all she said, before she fell to the floor. Then the seizure came over her, as it always did when she was afraid. As it had that night the policeman came to tell us Dad wasn’t coming home. Mumma gave a little shout of alarm and crawled towards Yada, trying to shield her head from hitting the skirting boards. All the while Yada’s body writhed and shuddered. Her skinny, black-stockinged legs kicked against the wall. My skin prickled and I wanted to turn away, to pretend I hadn’t seen her at all, to go back to the mirror and stare at my reflection, but my feet kept moving, taking me down the stairs until I was kneeling on the floor beside Mumma, waiting for Yada’s fit to end. While Mumma nursed her and Chooky wept, I waited.

Finally, Yada lay still. A trail of saliva shone silver on her cheek. She looked up at us with glazed eyes. She had stopped shaking but she was still somewhere else. I put my arm underneath her and tried to make her sit up but she pushed me away. It was too soon.

It took ten minutes before Mumma and I could help Yada to her feet and steer her back into the kitchen. I made a pot of tea and doused a cloth in cool water to wrap around Mumma’s bruised hand. Chooky came and sat under the table and rocked his body in a soothing rhythm, his thumb in his mouth.

I loved them all but it hurt too much. I loved them but I knew I would leave them.

7

HOLD THE RIGHT THOUGHT

Poesy Swift

Next morning, I woke to the sound of Yada calling, ‘Chook, chook, chook,’ and scattering scraps in the back yard beneath the plum tree. Chooky was out there too, shooing the hens towards the food, as if they couldn’t find anything without his help.

The kitchen was quiet. Mumma was still in bed, nursing her bruised hand. There was no butter but I scraped a thick lump of dripping from the tin by the stove and spread it on yesterday’s bread, set the kettle on the hob and measured tea-leaves into the old brown teapot.

Yada and Chooky sat either side of me and no one spoke. We were all listening to the house. It was as if last night’s argument was still echoing around the kitchen. Finally, Yada said, ‘I hope you held your mother in your thoughts.’

Chooky nodded but I stirred my tea and listened to the chink of the spoon against the china. I’d been holding my family in my thoughts all my life but it hadn’t saved my dad or healed my mumma’s broken heart or stopped Yada’s seizures.

Yada knew me too well. She knew the closed expression on my face. She took my hand and folded her fingers over mine.

‘Poesy,’ she said, ‘remember when I took you on the tram into the city to hear Mrs Besant?’

I nodded, ashamed that I remembered the excitement of walking past all the theatres more than anything that was said in Mrs Besant’s lecture.

‘There is no religion higher than truth,’ said Yada. ‘That’s what she told us. Your mother and I, we argue because we seek the truth. It is a fact that

we would have more pennies if you sacrificed yourself to the dreadful match factory. But in truth it would not lead us closer to happiness.’

I took a sip of tea and tried to avoid meeting Yada’s gaze.

‘But if there was some other way I could bring us pennies, everyone would be happier then, wouldn’t they?’

‘Pennies can’t make our happiness, child. Mrs Besant said the whole world, the whole universe, is only a Thought of God. Sometimes my thoughts overwhelm me but I am trying to treasure the strength of God to help me hold the right thought and discover the truth. If Adeline and all of us would simply hold the right thought, then we would defeat the forces that trouble us. Pennies won’t solve our problems. Each of us makes our world through our thoughts.’

Yada spoke softly, as if afraid that Mumma would hear. Since Yada had converted to Theosophy there had been battles for my faith as well as my future.

It made my head hurt to think anyone could change the world through their thoughts. But I held the thought of the Lilliputians in my mind. I held the moment where I had stood singing in Balaclava Hall and tried to imagine it happening again. Perhaps it worked. Later that morning, Mrs Essie came to the door.

Mumma and Yada shook their heads in disbelief when Mrs Essie explained why she had come. I stood very still, like a deaf–mute, waiting for Yada to start an argument, but she was too shy of Mrs Essie. She listened with her head to one side, her expression horrified. After Mrs Essie had left them with some papers to sign, the fight began in earnest.

Yada took the papers by one corner and dropped them in the basket for fire waste, as if they were filthy rags fit only for burning.

‘Oh Mother, it’s the stage or the match factory for her,’ said Mumma. ‘Why can’t you see that? The woman said thirty shillings a month. Thirty shillings! What would you have Poesy do here in Melbourne that would earn a fraction of that? And we’ll be spared her board and lodging if she’s away.’

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish Bridie's Fire

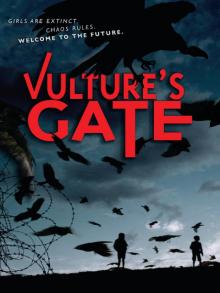

Bridie's Fire Vulture's Gate

Vulture's Gate The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie

The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie A Prayer for Blue Delaney

A Prayer for Blue Delaney The Year It All Ended

The Year It All Ended India Dark

India Dark Becoming Billy Dare

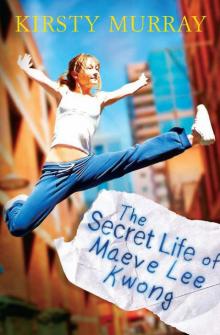

Becoming Billy Dare The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong

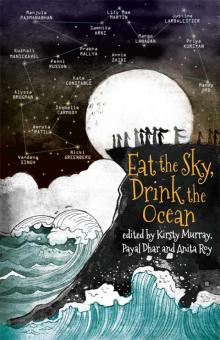

The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean