- Home

- Kirsty Murray

The Year It All Ended Page 19

The Year It All Ended Read online

Page 19

The German graveyard lay seven miles from town, through flat fields of devastation. As the sun rose, the poppies in the fields glowed like scarlet flame against the spring grass. Tiney felt as though she was walking through a dream. Along the verge, more red poppies were in bloom, as well as yellow buttercups and white Queen Anne’s lace. She passed along an avenue of ruined trees, tiny green leaves struggling to bud through the blackened, broken trunks. She crossed small bridges over creeks, hastily reconstructed, walked past craters and piles of rubble, shattered farmhouses with nothing but a single section of wall remaining, deep trenches where water pooled and lay stagnant, and thousands and thousands of graves. Some bore white crosses, others had scattered headstones. Everywhere she looked, there were graves.

The sun had well and truly risen by the time she reached Langemarck, where thousands of simple, unpainted crosses stretched across the field. A low hedge and a tangle of barbed-wire fences surrounded the cemetery. The slope from the road to the edge of the cemetery was slippery with mud and though she walked up and down the road, she couldn’t see a point of entry. Tiney knew that crossing any land without a marked path could be dangerous. She remembered the small boy at Villers-Bretonneux with one leg. Then she noticed an older woman dressed in black moving among the graves. She moved with purpose, cutting small briar roses from a hedge and placing them before the yellowing crosses. Tiney waved to her.

‘How did you get in?’ she called, first in English, then in German. The woman’s face relaxed when she heard Tiney speak German.

‘Up ahead, follow me, I’ll show you where I found a way through the wire,’ she said.

As they walked in tandem either side of the barbed wire, Tiney said, ‘I’m searching for my cousin’s grave. He’s buried here.’

‘My cousin is here too.’

The woman stopped at a small break in the hedge and then, wrapping her shawl around her hand, she pushed aside a large coil of barbed wire and gestured for Tiney to climb through.

‘My cousin, my brothers and my son are all in Belgian soil,’ said the woman, offering her hand to Tiney as she clambered up the verge. ‘There are more than a million German men and boys in Flanders fields.’

They walked together through the graves, both glancing from side to side to scan the tin nameplates tacked to the base of the crosses.

‘My cousin died in the first battle of Ypres in 1915,’ said Tiney. ‘My brother died in the Somme. I’ve already been there to find his grave.’

‘My husband died in the Somme. I’ve come to Belgium to find my cousin and my brothers, but especially to find my boy, my only son. He went missing in action in 1915. He was only eighteen. But you know, all these years, since he died, I can never feel he’s truly dead. Perhaps missing in action might mean he lost his memory and came to live among the people here. Sometimes, I dream that he is living in Belgium. Perhaps he has a Belgian wife and a little child.’

Tiney had seen enough of the battlefields now to know how easy it would be for a man to be listed as ‘missing in action’ but truly dead. She looked at the woman with such pity that the woman began to weep.

‘I must believe in this dream.’

‘Dreams are important,’ said Tiney, touching the woman gently on her shoulder.

Tiney remembered too well that feeling, that numbing disbelief that someone you loved so much could simply have been snuffed out. She remembered those moments of wanting to believe Louis’ death had been some sort of terrible joke, that at any moment a letter would arrive to say it was all a mistake, that he was alive and on his way home to Adelaide. And she thought again of the photo of the woman and child, the desperate longing to believe that they might have been connected to Louis.

The woman suddenly, unexpectedly, embraced Tiney. Tiney felt how frail she was beneath her widow’s weeds. Then the woman kissed her swiftly on one cheek and turned and hurried away. Tiney was left alone, surrounded by the yellowing wooden crosses.

When she finally reached the section of the cemetery that the Red Cross had designated as being where Will was buried, she discovered it was actually a mass grave. The tin plate simply said that the grave contained twenty-five soldiers. Her heart sank. She couldn’t take a picture of this for her uncle and aunt. Instead, she gathered up handfuls of wildflowers and covered the length of the grave. She worked with speed and purpose until the grave looked as decorated as Louis’ had been. Then she took a photograph of the blanket of flowers with her Brownie camera. Lastly, she knelt down and removed a small pinch from an envelope of poppy seeds that she’d gathered in the cemetery in Buire-Courcelles and buried them near the grave marker.

‘These are from Louis to you, Will,’ she whispered. She thought of the woman in black, running away from her through the cemetery of graves. ‘For you and the cousins and brothers and husbands and sons that are with you.’

The sun rose high overhead as Tiney pulled aside the barbed-wire coils and climbed onto the road again. As she walked through the sunshine, her shadow stretched out before her. In her mind’s eye she made a picture of Louis and Will walking alongside her, their shadows overlapping. And for the first time since that morning at Larksrest, the morning when Papa had come into the room a changed man and Mama had spilt her basket of plums across the floor, Tiney felt at peace.

Butterfly kisses

Tiney stepped off the train at Friedrichstrasse, into the bustle of a Berlin afternoon. She’d slept much of the way from the Belgian border, where a customs officer had taken her papers and shouted at her until she explained, in her best German, that she had come to visit her cousin.

From Ypres Tiney had travelled to Brussels, where she spent three miserable nights in a hotel. She had made the mistake of detailing her travel plans in the note she had left Ida, and when she checked in at the front desk she was given a stack of mail forwarded from Paris. There was a letter from her parents, one from Thea and, most annoyingly, a long letter from Ida begging Tiney to come back to Paris. There was also a slim white envelope from Geneva.

Tiney placed the letters from her family and Ida in her suitcase. Then she sat up all night writing a reply to Martin. His letter was as honest and intimate as their conversation in the restaurant. Even if he wasn’t interested in her romantically, at least she was sure he valued her friendship. She wrote back to him sharing every detail of her visit to Ypres and also gave him an outline of her planned visit to Berlin, though she knew he wouldn’t approve.

Berlin was beautiful in the afternoon light, with its elegant buildings, shops with plate-glass windows, and tree-lined boulevards. Trams and buses glided smoothly along the streets. There were no ruins, no dust, and no destruction. The bombs had never reached Berlin. Unter den Linden, a long boulevard of trees budding with green leaves, lifted Tiney’s heart for a moment but as she drew closer to Kurfürstendamm she began to notice that beneath the surface, the city was suffering. She saw a half-starved woman in black holding the hands of two skinny little children, and a barefooted girl with a wretched face leaning against the corner of a building dressed in nothing but her overcoat. Then Tiney passed a man standing on a street corner, begging. He had only one leg and one eye. The side of his head was bandaged with dirty strips of cloth. He held out a tin cup to passers-by, and Tiney could not bring herself to meet the gaze of his single blue eye.

Tiney was alarmed to find Hotel Elvira was both smaller and grubbier than she’d hoped. She checked in and then set off on her quest, crossing over the river into a network of narrow laneways, where the poverty of the city grew even more obvious. A pile of rags in the shadows of a deep doorway began to move and she saw the faces of an old woman and two small children peer out from amid the dirty cloth.

She stopped a girl, dressed in a tattered wool coat, and showed her the address that Onkel Ludwig had sent her, the address from which Paul had last written to his parents. The woman pointed down another shadowy laneway.

Inside the building, the paint was peeling from the walls

and a bitter dampness hung in the air. Tiney climbed to the second floor and knocked on the door of the apartment. It opened only a crack and a dark eye peered out at her.

‘Guten Tag,’ she said, using her best German, ‘I’m looking for Paul Kreiger. My name is Martina. I’m Paul’s cousin from Australia.’

The door opened wide and a thin, dark-haired woman stared at Tiney, her face lit with wonder and surprise. ‘Tiney Flynn!’ she cried.

From behind her skirts, a fair-haired boy peered up at Tiney. For an instant, Tiney was confused. Had Paul married a widow? Who was this woman and her golden-haired child? And then she knew. This was the woman in Louis’ photo, the woman holding the small baby, though the baby was now a boy.

‘You know me?’ said Tiney.

‘Your cousin talked of you often. He told me about you and your sisters and your brother Louis. This little boy, my son, his name is Louis also,’ she said, drawing the boy to stand shyly in front of her. ‘He is named for your brother.’

Tiney couldn’t think what it could mean. For a fleeting instance of longing, she wanted the boy to be Louis’ son, to be her very own nephew. But how could it be possible? How could Louis have fathered a child that was raised behind enemy lines and never written of it? And the boy looked too old. Louis hadn’t reached Europe until late in 1915, so no child of his could be older than four.

As if the young woman understood Tiney’s confusion, she said, ‘My name is Hannah. My son, his father is your cousin Wilhelm.’

Tiney felt her knees grow weak as she understood what the woman had told her. All the pieces of the jigsaw were falling into place. Hannah drew her through the open doorway and led her into the small apartment. It was simply a bedsit, with a bed in one corner, a long divan in another, a small table with three chairs, and one window overlooking the laneway. Hannah gestured for Tiney to sit down.

‘Will is alive?’ asked Tiney, hope and confusion brimming inside her. Could it be that he was not among the fallen at Langemarck?

Hannah hung her head. ‘No,’ she replied softly. ‘No, he died when our child was a baby.’

‘But my uncle sent me this address as Paul’s address. Do my uncle and aunt know about you and the baby?’

‘I’m not a baby,’ interrupted Louis. ‘I’m six years old!’

Hannah smiled and stroked the boy’s fair hair. ‘No,’ she said. ‘Wilhelm sent a picture of little Louis to your brother just before the war began. He was the only one who knew about our child until now, though Will also wrote to Paul and told him that we were engaged. Now Paul thinks it best not to tell your uncle and aunt. Not yet.’

‘But you must tell them. You must!’ said Tiney.

Hannah drew a deep breath. ‘Australia is so far away. Until Paul came and found me in Heidelberg, I couldn’t think of this family. I was Wilhelm’s fiancée, but never his wife. At first, we couldn’t marry because he was a student and I was a secret he kept from his parents. My father wouldn’t have countenanced it either – Wilhelm was a foreigner, a gentile. I ran away from home to be with him. Then the war began. And we were going to marry when he was next on leave. But he never came back. He never lived to give me and our son his name, so I couldn’t believe your uncle and aunt would accept me.’

Tiney didn’t know what to say. How would her uncle and aunt feel about a child born out of wedlock?

Hannah made them tea and they sat and talked as the afternoon slipped into evening. Little Louis played quietly on the floor and listened. Finally, when the sky outside the window had darkened, Hannah lit the gas wall lamp. She insisted Tiney join her and Louis for their evening meal and went downstairs to warm a pot of turnip soup in her landlady’s kitchen.

It was a simple, meagre meal and Tiney was embarrassed that she had arrived empty-handed. Louis scraped the bottom of his bowl and licked the spoon and Tiney offered him the rest of her soup, though she was still hungry.

Hannah was putting Louis to bed when the key turned in the lock and Paul stepped into the room. He frowned when he saw Tiney, almost as though he didn’t recognise her.

‘Guten Abend, Cousin Paul,’ she said.

Then Paul crossed the room swiftly and enveloped her in a hug. Tiney pressed her face against his dark wool coat smelling of tobacco and soap and hugged him back. All her irritation with him evaporated and when he held her at arms-length to gaze into her face, she smiled.

‘Did my parents send you?’ he asked.

‘Yes and no,’ she answered. ‘They paid my fare to Europe but they don’t know that I’m here in Berlin.’

Paul visibly slumped. ‘Then you haven’t brought me any cash, have you?’

‘What happened to your trust fund?’ asked Tiney.

Paul glanced over at Hannah, who was sitting on the bed, gently humming a song to Louis as he drifted off to sleep.

‘Let’s go out for a walk,’ he said. ‘I’ll escort you back to your accommodation. It’s not a good idea for you to walk the streets alone.’

Tiney whispered a hurried goodbye to Hannah, promising to visit again tomorrow. Then she put on her hat and followed Paul out into the dark street.

‘We must get you back to your hotel before curfew,’ said Paul. ‘Where are you staying?’

‘In a pension in Kurfürstendamm,’ said Tiney.

Paul looked surprised but said nothing. He seemed to be wrestling with what he wanted to say first.

‘Why didn’t you tell me, Paul?’ asked Tiney. ‘You knew, when I showed you the photo of Hannah and the baby, didn’t you? You knew who they were, but you said nothing.’

‘Will wrote to me from Heidelberg. He said he was in love with a woman, a Jewess called Hannah. He said he didn’t think our parents would approve, more because he was too young and was still a student than because of her religion. He didn’t tell me he was going to become a father. But when I saw the photo, that evening when you and I argued at Kaiserstuhl, I simply knew. She looked exactly as he’d described her in his letters. And if the photo was among Louis’ things, it would have been because Will had sent it to him before August 1914, which matched the date on the back. Will trusted Louis more than me, I suppose.’ Tiney heard a hint of Paul’s familiar bitterness.

‘Is that why you ran away? Because of the photo?’ asked Tiney. ‘But why didn’t you tell me?’

‘How could I? What if I was wrong? What if Hannah had married someone else and the child wasn’t Will’s? There was so much I couldn’t know. And I wasn’t sorry to leave, you know that.’

‘But why are you living in such poverty? Paul, that room, it’s not a fit place to raise a child.’

Paul hung his head. ‘I could only get access to one part of the trust. My father controls the rest and he won’t release it unless I come home.’

‘But if you told him about Hannah and Louis, then surely he would help.’

The streetlights made Paul look pale and wan. ‘I’ve found work in a nightclub, but everything is expensive when you’ve only got German marks and not foreign cash. I should have left Hannah and the boy in Heidelberg. But they were living in poverty there too. I thought I could offer them a better life here.’

‘Are you in love with her?’ asked Tiney.

Paul looked startled. ‘No. But she’s my sister-in-law in everything except name and Louis is my nephew. Wilhelm should have married her. He should have told our parents.’

‘Then why haven’t you told them?’

‘They’d never believe me,’ said Paul. ‘They’d think I’m just trying to get my hands on the trust.’

‘They’d believe you if they could see Louis. He looks so much like Will. No one could see him and not realise that he’s Will’s son.’

Paul didn’t reply but kept walking swiftly along the avenue. Kurfürstendamm at night was a different landscape. Cafes and bars cast golden light onto the pavement. Girls with painted faces and short skirts stood along the roadside.

Tiney pointed to the entrance of Hotel Elvira. ‘That’s

where I’m staying,’ she said.

Paul groaned. ‘You can’t be serious! What made you choose that flophouse?’

‘A friend of Ida’s in Paris stayed there before the war,’ said Tiney, feeling embarrassed.

‘Berlin was a different city before the war. We’ll get your suitcase and I’ll take you back to Hannah’s. I have to get to work soon and we both need to be off the streets before midnight. There’s still a curfew in place because of the putsch and the general strike.’

When Tiney asked for her suitcase at the pension’s reception, she found the lock on it had been broken and the contents rifled through. Paul cursed the porter but Tiney didn’t want to make a fuss. She was glad she’d carried all her cash and papers in her handbag.

Back out in the street, a group of women called out angrily to Tiney and Paul.

‘What did they say?’ asked Tiney, confused by their heavy accents.

‘They think I’m your pimp and we’re encroaching on their territory,’ said Paul.

‘They’re women of the night?’ asked Tiney, her voice squeaky with surprise. ‘They think I’m one too? Me?’

‘There are tens of thousands trying to sell themselves. How else can they feed their children?’

As they came to the next corner, a tall man stepped out of the darkness and Paul attempted to cross the road to avoid him. But the tall man quickened his pace and began to follow them. Tiney heard Paul mutter a curse under his breath.

‘Walk faster and don’t look back,’ said Paul. But they could hear the man’s footsteps drawing nearer. Tiney glanced over her shoulder and saw the man gesturing them to slow down.

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish Bridie's Fire

Bridie's Fire Vulture's Gate

Vulture's Gate The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie

The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie A Prayer for Blue Delaney

A Prayer for Blue Delaney The Year It All Ended

The Year It All Ended India Dark

India Dark Becoming Billy Dare

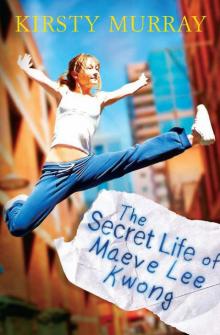

Becoming Billy Dare The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong

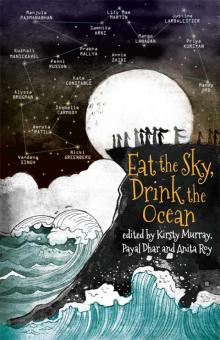

The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean