- Home

- Kirsty Murray

The Year It All Ended Page 16

The Year It All Ended Read online

Page 16

‘Call me Ettie, please,’ said Nurse Rout. ‘The Imperial Graves Commission has set up at the Red Chateau outside town and they might be able to help you. But I’m afraid there’s no accommodation here. Best to take the evening train back to Amiens.’ She looked at Mrs Alston with a particularly dubious expression.

‘A friend suggested it might be possible to pay for a billet with a local family,’ said Ida. ‘We’re happy to pitch in. We’re used to hard work. Tiney and I worked in the kitchens of the Cheer-Up Hut in Adelaide, and Mother’s a trouper. We could make ourselves useful cheering up the volunteers with the Australian Graves Detachment.’

Ettie Rout sighed, obviously not impressed. ‘I don’t think that would be possible. There aren’t many buildings with roofs on them yet – most families have only one or two usable rooms. They’re still using tarpaulins to cover the broken roofs and oiled paper in place of windows, and they burn bits of the house to keep themselves warm. However, if you’re game, I could offer you camp beds for the night in the cellar of the school. There’s little to eat here but if you’ll give us a hand with serving lunch to the children you’re welcome to join us.’

Inside the ruins of the old schoolhouse, dozens of raggedy children gathered around a long table. The room echoed with their shouts and the noisy clatter of spoons hitting against tin bowls. Mrs Alston was shown where the camp beds in the cellar were, while Ida and Tiney took off their coats and rolled up their sleeves. A soldier carrying two buckets of water from the town pump emptied them into metal tubs. Tiney and Ida set to work washing tin mugs, plates and spoons to serve the next round of children that arrived to be fed.

A small, dark-eyed boy came and stood beside Tiney, watching her with curiosity. She asked him in her schoolgirl French if he wanted something.

‘I would like some black coffee and a cigarette,’ he replied, in broken English.

Tiney laughed at first but when she looked into his face, she realised he was serious. Then she noticed he was using a crutch to support himself. The lower half of his left leg was missing.

When the children’s lunch was finished, Ettie invited Tiney, Ida and Mrs Alston to join the workers for a bowl of stew and a cup of tea. The stew appeared to be mostly made of tinned vegetables and the tea was both weak and oddly bitter but the bread that was served with it was still warm from the oven.

Ettie introduced them to her fiancé, a man called Fred Hornibrook, and a young Frenchwoman who was apparently the teacher of the raggedy children. As they ate, a ragbag assortment of soldiers in various uniforms came in and out of the building.

Mrs Alston stiffened when a group of German soldiers appeared in the doorway and then left again. Moments later, several Chinese men arrived carrying supplies that they piled up in a corner at Ettie’s direction.

‘There are about four thousand German prisoners and a Chinese labour battalion in the area,’ explained Ettie. ‘They’re working on the clean-up. The Chinese did most of the work rebuilding the railway line. The Australians here are volunteers who’ve chosen to stay behind and work with the Graves Detachments. They wanted to make sure that Australian soldiers buried their own rather than leave it to the British. But there are English and French soldiers too, still waiting to be called home – forgotten contingents. They keep body and soul together by selling army supplies to the villagers.’

‘And the Graves Commission is working out of this place called the Red Chateau?’ asked Ida.

‘They’re not very excited about civilians coming to the Front,’ said Fred Hornibrook.

‘Even if they aren’t welcoming, we have to ask,’ said Tiney. ‘We think Charlie may be in the Adelaide Cemetery.’

‘I’d take you there but I’ve injured my shoulder, worse luck. Let’s go outside and see if there’s a vehicle available or a man who could take you out in my little trap.’

In the ruins of the town square, they saw a line of elderly women struggling under the weight of buckets of water taken from the town pump. Tiney helped one silver-haired old woman and Ida another, while Fred tried to organise transport for them.

Suddenly, a motorbike came roaring around the corner and pulled up outside the depot, sending a spray of mud into the air. When the rider pulled off his leather cap and goggles, Tiney knew him instantly.

‘Martin Woolf, well, I’ll be blowed!’ called Fred Hornibrook, striding across the road to shake his hand and clap him on the shoulder.

‘Isn’t that your big bad wolf from Beachy Head?’ asked Ida.

‘Don’t, Ida,’ said Tiney. It was the strangest feeling to see Martin in this place, as if they were meeting again on another planet rather than in another country.

‘Hello again,’ said Martin, smiling directly at Tiney.

‘Hello,’ she replied, annoyed that her voice sounded squeaky and childish. ‘I wanted to write a note to thank you for your letter but you didn’t provide a return address.’

‘I was about to leave England for some months,’ he said. ‘I could have given you an address in Paris or Geneva but I thought that would require a rather long explanation.’

At that moment, Ettie came outside. When she saw Martin she let out a shout of pleasure and ran over to embrace him. Tiney looked at the ground and felt strangely deflated as Ettie and Martin chatted like old friends.

‘I wonder if you could hitch up Fred’s trap and take these ladies out to the Red Chateau,’ said Ettie.

‘For you, anything,’ he said. Ettie laughed.

Tiney set her lips firm, determined not to mind how they spoke to each other. ‘I’m sure if you could just take us to the Adelaide Cemetery, we’d be able to find Charlie’s grave ourselves,’ she said.

‘If you have a letter from the Imperial Graves commission, I could spare you the unhappiness of a long search,’ said Martin. ‘I know the Adelaide Cemetery well.’

He was looking at Ida and Mrs Alston as he spoke and Tiney felt moved by his compassion for them.

In the end, Martin and Fred went to collect the trap together. A truck drove past and a terrible odour caught Tiney unawares, making her feel a little dizzy. It was of earth and mud and mould and something else she couldn’t quite identify. She saw Ettie’s gaze flick towards the truck and away again.

‘I should warn you,’ said Ettie, ‘the reason they try to ban civilians from visiting the battlefields is that you might experience something very disturbing. I was surprised Martin sent you to me. Last year, when he was working here with the Graves Detachment, an Englishwoman went into shock when she came across the remains of her son. They’ve exhumed thousands of bodies and they’re trying to identify them, but it’s going to take years to set things in order. You must brace yourselves for some difficult sights. You’re very lucky that your young man is in a marked grave.’ Then she shook their hands and went back into the Red Cross tent. As soon as she was out of sight, Mrs Alston grabbed Ida by the arm.

‘Do you realise who that terrible woman really is?’ whispered Mrs Alston, her voice catching as she spoke, as if she might choke. ‘The Archbishop of Canterbury described her as the wickedest woman in the whole of the British Empire!’

‘She doesn’t seem either terrible or wicked to me,’ said Ida. ‘She seems quite kind, even if she isn’t very elegant.’

‘She must be awfully brave to stay in this place,’ said Tiney, trying to steer the conversation into calmer waters. ‘It’s as if the war isn’t over.’

As if to confirm Tiney’s statement, another explosion from a distant field made the three women jump.

Recovering from her shock, Mrs Alston drew herself up to her full height. ‘That’s all well and good, but that woman, who is living in sin with that Hornibrook chap, is the same person who stood on the railway platforms of Paris handing out prophylactics to the soldiers. And she gave them cards of “recommended” houses of shame to visit.’

‘Well, bully for her,’ said Ida. ‘I think I recall reading about her now. She was trying to stop them comi

ng home with dreadful diseases. I should have thanked her for sparing me and all my friends an awful fate.’

Tiney smiled, reminded of why she liked Ida so much. Ida and Mrs Alston glared at each other. Then Tiney stepped forward and laid a hand on each of their arms.

‘We’re here for Charlie,’ she said. ‘Let’s find him.’

Just then, Martin drove a tired old mule and trap around the corner of a ruined building. The trap was a two-wheeled gig with a single long seat at the front and a small dicky seat at the back. Martin helped Mrs Alston and Ida onto the bench seat and then looked at Tiney apologetically. ‘I’m sorry, Miss Flynn,’ he said, frowning.

Tiney smiled. ‘I’ll be perfectly happy riding backwards.’

He lifted Tiney up and placed her on the seat as if she were a small child, but then he looked into her eyes and smiled and she felt a shiver of certainty that he saw her as a woman.

As they bumped along the pot-holed road, Tiney’s stomach grew hollow. Across the fields lay the skeletal haystacks of barbed wire and deep gullies of mud. A few tufts of green sprang out of the dull ground but there were thousands of wooden crosses stretching in every direction as far as the eye could see.

When they reached the entrance of Adelaide Cemetery, Martin helped them down from the trap and led them through the gates. Though Ida and Mrs Alston had chatted to Martin on the drive out, they fell silent now. Martin took Mrs Alston’s note from the Imperial Graves Commission with the information about where Charlie was buried.

‘Stay on the paths,’ he warned.

‘Miss Rout has already told us about the danger,’ said Ida, sounding surprisingly meek.

‘It’s not only the bombs you have to be careful of,’ said Martin. ‘There’s broken ground you might stumble on, and things that don’t bear thinking of beneath this earth.’

They passed through the gates of Adelaide Cemetery; the graves stretched out silently before them, thousands of small, white crosses contained in a few acres of ground. Every now and then there was a distant explosion, as if the echoes of war would never let the bodies rest.

Tiney took out her Kodak Brownie camera, Minna and Frank’s farewell gift. Staring down through the viewfinder made her feel steadier. A distant line of ragged trees starting to bud in a lopsided way seemed the only living thing for miles. Flat, stricken fields stretched on either side of the cemetery. Tiney didn’t want to include this surrounding desolation. She adjusted the focus of the camera onto a single grave and pressed the shutter.

Most of the graves had tiny, flimsy wooden crosses on them but some had larger ones, placed by comrades or family members who had been among the early pilgrims to the cemetery. Ahead of her, Ida, Mrs Alston and Martin Woolf had come to a stop.

The cross on Charlie’s grave was dwarfed by the size of the two larger ones on graves either side. There was barely twelve inches between the placement of one marker and the next, and when Mrs Alston fell to her knees she was obliged to kneel on the other soldier’s grave. Ida knelt down beside her and put her arm around her mother. Tiney raised her camera to take a picture but then lowered it quickly. It was too intimate, too personal. Tears spilled from her eyes.

‘Let’s give the Alstons a little time,’ said Martin and he gently steered her between the lines of graves.

Further along the path, an old woman was slowly walking between the white crosses, peering at each one. A spray of violets lodged in the black band of her hat quivered as she wove her way through the cemetery. As Tiney and Martin drew closer they saw the woman was clutching a wreath and that she was trembling.

‘I won’t be a moment,’ said Tiney, turning away from Martin.

‘I don’t know where to lay his flowers,’ said the old woman, glancing up as Tiney approached.

‘Do you have a letter with directions? Perhaps we can help you find him if you tell us the number of his grave.’

‘But no one knows where my Walter rests, dear,’ said the woman. ‘They never found him. My Walter could be under any one of these crosses. You see, he’s in an unmarked grave. A mother should be able to sense where her boy is resting, shouldn’t she? But I don’t know which to choose. I only have to choose one, one that says that an unknown soldier lies resting there, and that may be my Walter’s grave.’

The old woman looked into Tiney’s eyes, pleading. Tiney thought for a moment and then said, ‘Perhaps we could choose one together.’ She took the woman’s frail hand in her own and led her back to the grave that Tiney had first photographed. Martin walked behind them and the sense of his presence made Tiney feel strangely braver.

Tiney picked a small spray of wildflowers and together she and the old lady knelt down, side by side, and laid flowers on the grave of an unknown soldier.

Fractured

On the drive back to Villers-Bretonneux, they passed a detachment of soldiers loading hessian sacks into the back of a truck. Tiney understood what this meant, but she still found it almost impossible to believe that the contents of those limp sacks had once been living, breathing men.

‘Don’t look too closely, Miss Flynn,’ said Martin, as if he sensed Tiney’s thoughts, though his eyes were on the road ahead.

Martin glanced across at Mrs Alston, his brow furrowed. She hadn’t spoken a word since they’d left the cemetery, and her eyes were glassy. Her fingers were entwined with Ida’s and they both stared ahead at the dusty road back to the town.

That evening, after a simple meal of canned food, Mrs Alston quietly gave Ettie Rout a roll of francs.

‘For the children,’ she said.

Ida helped her mother downstairs into the cellar of the schoolhouse. A single candle on a wooden box lit the space. Ida lay down beside her mother on one of the narrow camp beds and they held each other silently.

Tiney could hear the subdued tones of Ettie Rout upstairs, and the soft rumble of men’s voices. Leaving the Alstons to their grief, she climbed the stairs. Ettie, Fred and Martin were sitting with some soldiers, drinking from tin cups. Tiney sat on a stool beside Ettie and gratefully accepted a mug of black tea. One of the soldiers sitting next to Fred was trembling, his hands shaking as he raised a tin mug to his lips. The room felt close with the scent of men and whisky. Tiney took her cup and went to stand by an open doorway. Outside, in the town square, the shouts of drunken soldiers reverberated against the ruins of the buildings.

Martin came and stood behind her. ‘Some of these men are traumatised by the work. In the evenings, drink is their only escape. You can’t judge them for it.’

‘I wasn’t judging anyone,’ said Tiney.

Martin shrugged. ‘Many would.’

‘If you knew me better, you’d know I’m not like that.’

‘I’d like to know you better,’ he said.

Tiney shifted uncomfortably from one foot to the other.

‘But I didn’t come to Villers-Bretonneux expecting to find you here,’ said Martin, ‘if that’s what you’re thinking.’

‘You’re not a very good mind-reader after all,’ said Tiney, though he had read her hopes so clearly that she squirmed.

‘I’m en route to Paris,’ said Martin. ‘I detoured here to see Ettie and Fred. They’re going to London next month, and I wanted to see them before they left.’

‘How do you know them?’

‘I was with the Australian Graves Detachment last year for a few months. It’s a labour of love but soul-destroying too. The volunteers try to work out who the men were, from tattoos or from markings if their uniforms are rotted away.’

‘It doesn’t bear thinking of,’ said Tiney.

‘It’s ugly work but we want to do the right thing by our mates. It makes me sick at heart we’ll never know who all of them were. On my last week of service, I found two men from the Eleventh Field Ambulance, men that I’d worked alongside. It was a relief to know that they, at least, would rest in marked graves.’

A drunken soldier came stumbling through the darkness towards the canteen. Tiney

moved away to let him through the door but he fell in a heap beside the entrance and sat with his head in his hands. Martin stepped outside and squatted down beside the man, offering him his mug of tea. Tiney slunk back to the fire and sat quietly to one side.

After Martin had guided the drunken soldier into a corner of the room to escape the cold night, he came and joined Tiney by the fireside.

‘Is he all right?’ asked Tiney.

Martin shrugged. ‘Some of these men have simply been forgotten. There are British soldiers left behind in charge of dumps of cars and ammunitions that have been completely abandoned by the army. The soldiers sell off what they can to the peasants in exchange for food and then spend the rest on drink.’

‘Were you driven to drink when you worked here?’

‘I was driven to the edge of despair.’

‘Then why have you come back to France?’ asked Tiney. ‘Why don’t you go home?’

‘I’ve been working with the League of Nations Union in London. I’m on assignment for them now. Keeping the peace is a far greater challenge than winning the war.’

‘But your family must be longing to see you,’ said Tiney. ‘They must be so proud of you.’

Martin didn’t meet her gaze. He stared into the fire and the light flickered in his dark eyes. ‘You know they called it “The War for Civilisation”, but it turned men into beasts. How can anyone be proud of that?’

‘I’m proud of my brother,’ said Tiney. ‘And of Charlie Alston and all the men who died for us.’

‘You aren’t responsible for your brother’s death, Tiney.’

Tiney recoiled. ‘That’s not what I meant. But he fought to protect me, to protect Australia.’

‘Do you really think that was what the war was about? You told me, when we stood on the cliffs of Beachy Head, that you weren’t naive.’

Tiney was suddenly so unspeakably angry that she couldn’t reply. She stood up abruptly, dropping her tin mug on the stone floor. Everyone turned in surprise at the clattering sound.

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish Bridie's Fire

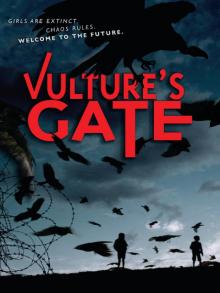

Bridie's Fire Vulture's Gate

Vulture's Gate The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie

The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie A Prayer for Blue Delaney

A Prayer for Blue Delaney The Year It All Ended

The Year It All Ended India Dark

India Dark Becoming Billy Dare

Becoming Billy Dare The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong

The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean