- Home

- Kirsty Murray

A Prayer for Blue Delaney Page 10

A Prayer for Blue Delaney Read online

Page 10

‘What do you mean?’

Bill put his hands on Colm’s shoulders and looked him square in the face. ‘I reckon you ought to call me Grandad from now on. That way no one is going to go asking us questions, eh? I don’t have any grandkids of my own, but if I did that’s what I’d want them to call me - Grandad.’

Colm smiled. It felt strange to be so happy after all the tears of the day before, to feel the warmth of it fill him up like sweet tea.

‘All right, Grandad,’ he said.

18

The Dog Fence

There was plenty of time to think in the long drive across the Nullarbor. Sometimes Colm could hear Doreen crying over the roar of the engine. Rusty flattened her ears at the sound and pushed her snout against Colm’s hand. She didn’t like it any more than Colm. When Jimmy shouted ‘Nani, Nani’, over and over again, Doreen’s voice became a hum of comforting sounds. Colm pulled out his harmonica and played the happiest tunes he could think of in the hope it would cheer everyone up.

Colm found himself practising the word ‘Grandad’ over and over again. When they stopped to camp overnight and Bill handed him a plate of beans for his dinner, Colm said, ‘Thanks, Grandad!’ so loudly that both Bill and Doreen laughed, for the first time since leaving Kalgoorlie.

At the train station in Ceduna, Doreen took Colm’s face in her hands and kissed him on the forehead. Colm shut his eyes and took in the warmth of her skin, the dusky scent of her hands.

‘You take care of that old bugger,’ she whispered. ‘And if you get worried out there in that desert, you look up at the Seven Sisters and let them light your darkness, eh? And we both say our prayers and maybe Rosie‘ll find her way home again soon.’

The train pulled out of the station and Jimmy stood on Doreen’s lap and pressed his face against the glass, waving at Colm. Colm waved back.

‘It was a good thing you saved Jimmy,’ said Bill. ‘I reckon Doreen’s heart would have broken without a little one to take care of.’

‘But I didn’t save Rosie,’ said Colm.

‘A man can only do his best and your best was bloody good,’ said Bill.

As they drove out of Ceduna, Bill said, T heard from an old mate that there’s work going along the Dog Fence, filling in for one of the regular patrollers. Thought I might take it on. No one will come chasing us along that lonely stretch of country. Gotta let my reputation as a preacher settle down too. I’m overdue for a bit of peace and quiet, so the desert’s the place for us.’

The Victoria Desert began to unfold as they drove further away from the town. They headed north to the Dog Fence, through a wide, open landscape of earth and sky. Colm fiddled with the catch on the glovebox and flipped it open. Instantly, he saw that the old black Bible was missing. The thought of the long weeks of driving without it made his heart sink.

‘Where is it?’ he asked.

‘Where’s what?’ asked Bill, innocently.

‘The Bible. The black one. My Bible,’ said Colm.

‘Reckon it got left behind at the two-up school.’

‘You left it?’

‘Forgot to put it back. You don’t want that old thing. You know those stories inside out. Tell you what, next town we get to, well, that won’t be for a long stretch, but when we do, I’ll buy you a book of funnies and a nice fat collection of my old mate, Henry Lawson.’

Colm couldn’t believe it. How could Bill have forgotten his Bible? He looked at him sideways, wondering how deliberate the forgetting had been. Worst of all, the photo of Blue Delaney had been tucked into the Bible between the pages of the Book of Ruth and now it was lost forever. He pulled out his harmonica and blew a long, mournful note.

It was slow and hot travelling along the Dog Fence. The further they drove inland, the hotter the air grew until Colm felt he was breathing fire. It was like being in a furnace. He and Rusty tried sticking their heads out the window, but it was worse than the still, burning heat inside the car. The gritty air scoured Colm’s skin and made his eyes sting. He pulled his head back inside. The few stunted trees were twisted and tortured by the sun. There was nothing to see except saltbush, pigface, tough little grasses struggling to sprout through the rock and sand, and the fence stretching like a thin grey scar across the landscape. Tin Annie seemed to moan as she struggled over the unforgiving ground.

‘What if we break down?’ asked Colm.

‘Don’t you worry about that. They used to do the fence on camel, but these days they use jeeps. Tin Annie here, she’s part camel with a bit of jeep thrown in, so she’ll be fine.’

‘But what if we get lost?’

Bill looked amused. ‘We’re following the fence, mate. It’s more than three thousand miles long and there’s no detours. Doggy Burton knows where we are and if we didn’t check in on time, he’d send someone out. Just enjoy the ride.’

Bill pulled over next to the fence where an emu had crashed into the wire. They both climbed out of the ute to inspect the carcass.

Bill shook his head. ‘She’s hit the fence mighty fast, this one. Looks like she broke her neck.’ The emu was already rotting. Colm had to cover his nose and mouth with his hand to stop the foul smell searing his nostrils.

In the distance, another emu was running across the gibber desert. ‘See, they get speed up. They can go 30 miles an hour but they don’t see the fence until they’ve hit it.’

Colm helped Bill sort through the tools he would need for the job and then climbed back into Tin Annie to wait while Bill repaired the fence. Further along they stopped to fill in a hole made by a hairy-nosed wombat. The day dragged on. They drove so slowly that Colm got dizzy looking at the fence. When he shut his eyes, he saw the endless mesh passing along behind his shut lids. Despite the flies and the heat, he fell asleep. When he woke up, it was to the sound of Bill hammering at a fencepost.

Colm’s shirt was sticking to his back, wet with sweat. He went round to the back of the ute and took a long drink from the billycan. The water was as warm as tea, but it was good to wet his throat. Flies buzzed around his face and no matter how hard he tried to swat them away, they came back and clustered around his eyes and mouth. Colm felt as if he was inside a strange and frightening dream. He wished it was night so that he could look up at the Seven Sisters.

That evening, Bill made the fire from mallee twigs that Colm had gathered. When the wood had burnt down, he raked the coals over and buried some potatoes deep in the red heart of the fire, then opened a long-necked bottle of beer. Colm scowled.

‘Do you have to drink that every night?’

‘A fella deserves a beer after a long working day, doesn’t he?’

‘I don’t want to drink any beer. Ever.’

‘No one’s saying you will.’

‘Drinking makes you forget things. You’re always forgetting things,’ said Colm.

Bill laughed and took another swig. ‘That’s the whole point, cobber. When you grow up, you’ll understand. It’s an art, knowing how to forget.’

‘Forgetting isn’t a good thing. I ask God to help me to remember everything. I ask in my prayers.’

‘Bully for you. But it doesn’t cut that way for me. If there was a saint of forgetfulness, I’d be praying to him for his guidance, but without the angel of forgetting I have to find my own ways and means.’

He threw a couple of thick slabs of meat on a rack and turned his back on Colm. Colm went and sat on the running board of Tin Annie and traced a pattern in the dirt.

Despite the weeks spent sleeping on Nugget and Doreen’s verandah, Colm still didn’t feel comfortable sleeping outside. Everything about this desert made him feel small, from the endless shimmering horizons to the vast starry night skies. A shooting star streaked across the sky. Colm pressed his hand against his chest. The world was too big, too hard to encompass. He wanted something small to think about. He pulled open the glovebox, wishing that his Bible would magically appear, but the only thing that caught his eyes was Bill’s old cigar box. Bill

usually kept it in a box in the back of the ute along with his tools.

He flipped open the cigar box and raked through its contents. There was a compass, Bill’s tobacco pouch, a couple of blunt pencils, a bottle of ink and a fountain pen, a single-edge razor blade - and a small piece of silky ribbon. He’d never noticed it before. It was connected to the bottom of the box. When he tugged at it, the bottom lifted up to reveal a secret compartment. Guiltily, he glanced across to Bill, sitting drinking by the campfire. There was a small stack of crisp pound notes in the secret compartment, a couple of official-looking forms folded in half and a small photo. The lost photo of Blue Delaney! He studied it in the half-light. Even though it was shadowy in the car, he could make out the brightness of her face. When he folded his hands to say his goodnight prayers, he added a prayer just for Blue Delaney, that God would keep her safe until he had a chance to meet her.

The days wore on, long and monotonous. Colm’s neck was sore from always turning his head one way to watch the fence. After a few days, Colm took over filling the wombat holes while Bill patched holes in the wire mesh. They topped up the water containers at every dam or tank, and ate tinned corned beef and tinned vegetables until Colm felt he couldn’t take another mouthful of them. The nearest town was hundreds of miles away and it would be a long wait for the promised book of comics or anything interesting to eat or drink.

One morning, Rusty wasn’t in camp when they rose. Colm helped Bill pack up the breakfast dishes, all the while scanning the low scrub, looking for a sign of movement.

‘Where is that damn dog?’ said Bill. He put two fingers into his mouth and blew a long, piercing whistle. Nothing moved.

‘I’ll find her,’ said Colm. He trotted out into the low scrub and then stood very still. If he shut his eyes and willed it, then he should be able to feel Rusty wherever she was. He folded his arms across his chest and frowned in concentration. He was sure she was close by.

When he opened his eyes, he noticed a tiny flicker of dust. Rusty was lying under a bush, twitching violently, her eyes rolled back and a trickle of saliva pooling in the dirt beside her mouth.

‘Grandad,’ called Colm, urgently. ‘Grandad, here, I’ve found her! But something’s wrong! Hurry!’

Bill knelt beside the dog. When he ran his hands over her body, Rusty jerked beneath his touch.

‘What is it?’ asked Colm.

‘Snakebite, maybe. Then again, maybe not.’

Rusty started convulsing uncontrollably, her whole body fitting and shaking as if charged with electricity. Her eyes flashed nothing but white and saliva frothed in her mouth. Colm grew cold with fear.

‘What’s wrong?’ he cried, feeling tears prick his eyes.

‘I reckon she’s taken dingo bait. Poison. It might be a kindness to put her down.’

When the seizure had passed, Bill scooped the dog into his arms and cradled her against his chest. ‘My poor pup,’ he said.

Colm walked beside Bill as he carried Rusty over to the ute and laid her on her blanket in the back. Bill reached across for the knife he used to butcher rabbits.

‘No! What are you doing!’ Colm grabbed Bill’s wrist. ‘We have to save her.’

‘For chrissake, get out of my way,’ said Bill, pushing Colm aside and taking hold of Rusty’s head. Quickly, deftly, he slit cuts on the side of Rusty’s ears. Blood flooded down, matting her fur.

‘Now go and fill the billy.’ Bill thrust the can at Colm, and then rummaged for something in the food supplies.

Colm ran to the canvas waterbags that were strapped to the front of the car. When he returned, Bill threw two fistfuls of salt into the water and stirred it up.

Rusty was fitting violently again, but when the convulsion had run its course Bill took her in his arms and squatted down, holding her firmly between his knees. ‘Now I’ll keep her jaw open. I want you to tip that salty water straight down her throat.’

Colm tried to keep the water flowing steadily, even though his hands were shaking. The salt water made Rusty vomit. When Bill set her down in the dirt, she staggered around the ute, throwing up over and over again. As soon as Rusty was up to it, they poured more salt water down her throat. Finally, when she’d finished, Bill carried her over to the lone mallee tree and laid her on her old blanket in the shade. Rusty started convulsing again. Between fits, her hind legs curled up beneath her in a painful cramp. Bill and Colm knelt beside her, rubbing her down, massaging the constricted muscles to offer some small relief. But the fitting went on. Colm felt it was never going to stop. His hands were sore from working on Rusty’s knotted muscles, and sweat poured off him.

‘Here, you need a break,’ said Bill. ‘Go get yourself a drink and rest in the car. I’ll call you if I need you.’

‘What are you going to do? You can’t shoot her, Grandad. You can’t.’

‘Settle down. I’m hoping it won’t come to that.’

Colm walked back to Tin Annie, fighting back tears.

The morning grew hotter. For a while, Colm fell asleep and then, when he woke, felt ashamed. He took the photo of Blue Delaney out of the glovebox. It wasn’t a holy card, but at least it was something. He put the photograph inside his shirt pocket and prayed as hard as he could. He was still praying when he heard the sound of Rusty barking - a thin, hollow sort of bark, but a bark. It sent him racing across to where she lay with her head resting in Bill’s lap.

‘I prayed for her,’ said Colm. ‘Maybe it helped.’

‘Maybe it did,’ said Bill. ‘Between your prayers and my hard work, she’ll be back to her old self in no time.’

That night, Colm stayed by the fire with Rusty nuzzled up against him. He didn’t want to get back into Tin Annie to sleep.

‘Reckon that old dog needs both of us tonight,’ said Bill, as if he could read Colm’s thoughts.

‘I’ll get my swag,’ said Colm.

He rolled out a thin flock mattress on the ground and then plumped up his battered pillow. Rusty sighed as Colm tucked the blanket around her and snuggled up close. Lying beside her, he savoured the warmth of the campfire on his face and the starry blaze of the night sky above.

When Bill’s steady breathing changed to snores, Colm pulled out the photo from his pocket and angled it towards the flame. He liked seeing the bright face by firelight, the way Blue Delaney was smiling with her mouth slightly open, as if she was about to laugh at something the photographer had said.

‘Thanks, Blue,’ he whispered. He was sure his prayers had helped save Rusty. He looked up at the Seven Sisters and felt that someone, somewhere, was looking out for all of them.

19

Dare and McCabe

Something changed during the next few days, something deep inside Colm. As they travelled further inland, the mallee was replaced by red dirt and spinifex and then the spinifex gave way to stony gibber desert and saltbush. At the same time, the way Colm saw the desert, the way he saw his place in it, began to shift. Perhaps it was the silences, the long hours where they were both concentrating on the fence. Perhaps it was the spirit of the ancient stones, the red soil, the far horizons. It felt so timeless, as if it had been there forever and time had no meaning. And then, in the early mornings, or late in the evening when Tin Annie was quiet, he was sure he could could hear the voice of the landscape. It sang in a low, sweet hum. If he stood quietly, he could feel the song move right through his skin. It was as if the desert got inside Colm. He didn’t feel frightened of it any more. He could hardly remember the things that used to scare him. The past receded into a small speck on a lost horizon, and every morning was like a new beginning.

It was slow work, repairing the fence, and there were days on end when they didn’t see another living creature. On a couple of occasions, they stopped at a homestead to replenish their water or catch up on news from the outside world. But for Colm, none of the news seemed real. It was as if the people they met were all aliens and the only real world was the one that he and Bill shared with Rusty.

<

br /> One night when they were camped in a flat, open stretch of country, a great arc of fire shot across the sky above them.

‘Sweet Jesus,’ said Bill, jumping to his feet. Rusty began barking.

‘What is it?’ said Colm.

‘Rocket fire,’ answered Bill, shaking his head. ‘There’s bad business going on out there. Getting ready for another war, they are. Testing some new murderous weapon. When I was a younger man, I fought in the war to end all war. But looks like it didn’t end anything.’

‘I think my Dad died in the war when I was a baby. Maybe that’s why it was just me and my mum. That’s not the war your Clancy died in, is it?’ asked Colm.

‘My Clancy . . .’ Bill looked away, out into the desert night. He seemed smaller, his shoulders hunched up, his fists clenched. ‘I’ve lost so many people, boy. Sometimes, it feels like the shadow of everyone that’s gone steals away all the brightness of those left behind.’

‘Do you think that’s maybe why my mum left me at the orphanage?’ asked Colm. ‘Because of my dad’s shadow?’

Bill looked startled, as if he suddenly realised that he hadn’t been talking to himself.

‘No, cobber. Don’t you listen to the ravings of a foolish fond old man. You settle yourself down and get some sleep.’ He knelt beside Colm and reached to tuck the blanket around him.

‘What’s that there?’ he asked, pointing to the photo of Blue Delaney lying on Colm’s pillow.

‘Just a picture,’ said Colm, snatching it up. ‘It’s nothing.’

‘Mind if I take a look?’

Colm hesitated. He pressed the image against his chest, hiding it from view.

‘It’s a picture of my mother,’ he said, listening to the sound of the lie and trying hard to believe it.

‘You didn’t tell me you had a picture of her,’ said Bill.

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish

Zarconi’s Magic Flying Fish Bridie's Fire

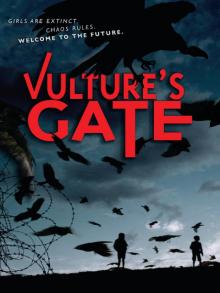

Bridie's Fire Vulture's Gate

Vulture's Gate The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie

The Four Seasons of Lucy McKenzie A Prayer for Blue Delaney

A Prayer for Blue Delaney The Year It All Ended

The Year It All Ended India Dark

India Dark Becoming Billy Dare

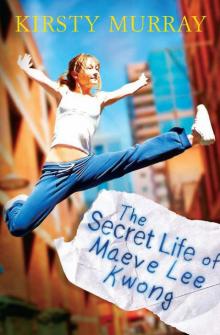

Becoming Billy Dare The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong

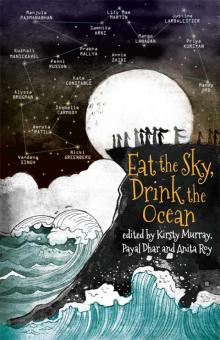

The Secret Life of Maeve Lee Kwong Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean

Eat the Sky, Drink the Ocean